By AL JAZEERA

Senegal is gearing up for elections – something that was far from certain just a month ago.

More than seven million people in the West African nation are registered to vote on Sunday to pick a successor to President Macky Sall, who has been in power for 12 years.

Vying for the country’s top job, 19 candidates have been campaigning for the last two weeks in a tight electoral race. For the first time since Senegal gained independence in the 1960s, none of the candidates is a sitting president.

While no clear frontrunner has emerged, analysts have said that the very fact that elections are taking place comes as a relief to many.

The lead-up to Sunday’s vote has been marred by a fair share of political drama. Originally scheduled to take place on February 25, incumbent Sall plunged the country into chaos last month when he announced he was delaying the vote to December.

The move sparked deadly protests, as well as pushback from the opposition and Sall’s critics, who saw the delay as an attempt to breach the country’s constitution and bypass the president’s two-term limit.

Eventually, a decision by the Constitutional Council to overrule the postponement led to Sall setting March 24 as election day. But the debacle has shaken Senegal’s reputation as a stable democracy in an often politically volatile region.

“People want Senegal to set the tone for the rest of the region and they want to make it clear that when your mandate is over you have to go,” said NDongo Samba Sylla, head of research and policy for IDEAs, a network of political and economic analysts.

More than 16,000 ballot boxes will be open across the country from 08:00 to 18:00 GMT on Sunday. To secure the top job and avoid an election run-off, a candidate will have to win more than 50 percent of the vote.

Who are the main candidates?

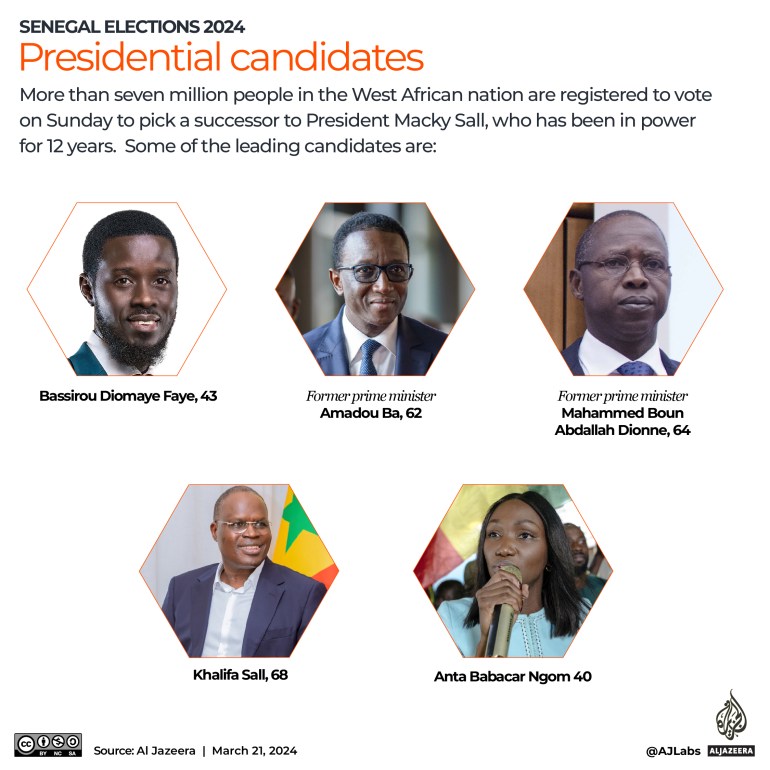

Leading the main opposition coalition is Bassirou Diomaye Faye. The 43-year-old has stepped in to replace opposition leader Ousmane Sonko, who was barred from running in the elections due to defamation charges.

Faye and Sonko have been the most popular figures in the lead-up to the elections.

Their experience as tax administrators has boosted confidence from peers that they will tackle corruption, push for accountability and promote a more equitable distribution of the country’s resources. They have also made bold statements about possible monetary reforms and the renegotiation of mining and energy contracts.

The duo has introduced itself as an anti-establishment force wanting a radical rupture with the previous government. However, analysts warned that their tone will soften should they reach power.

“Their radical discourse will likely change significantly if they get in power as they will have to compromise with actors who will be key for them to govern,” said Gilles Yabi, founder and president of WATHI, a think tank in West Africa.

Another candidate is former Prime Minister Amadou Ba, appointed by Sall as the ruling party’s presidential choice. He is seen as an orthodox figure who held several positions of power before. A victory for Ba would mean policy continuity with the previous government, something that would assure foreign investors. Yet, he is from the ruling Benno Bokk Yakaar (United in Hope) coalition whose popularity has been eroded by years of human rights setbacks.

There is also former Prime Minister Mahammed Boun Abdallah Dionne, who has called himself the “president of reconciliation”, and two-time mayor of Dakar, Khalifa Sall who is running for the fourth time.

The only female candidate is businesswoman Anta Babacar Ngom – a political newcomer who runs Senegal’s largest poultry company.

What are the key issues?

Despite the country being regarded as one of the fastest-growing economies in the continent, the perception among ordinary Senegalese is that wealth has not been equally distributed.

People have shown dissatisfaction with the country’s economic management as inflation has been slow to decline. More than 60 percent of Senegalese believed in 2023 that the economic situation in the country was bad, nearly double compared with the previous year.

Youth unemployment is going to be a major concern for the new president, as it has been for the previous one. Three out of 10 Senegalese aged 18 to 35 are jobless, according to a report from Afrobarometer. The crisis is further exacerbated by the speed at which the population is growing – it doubles every 25 years, it added.

Amid a lack of prospects and with about a third of the population living below the poverty line, the number of those trying to leave Senegal on crumbling wooden boats surged last year and nearly 1,000 died in the first six months of 2023, according to Spanish migration watchdog Walking Borders.

Another issue is the excessive concentration of power in the hands of the president – a key criticism of outgoing leader Sall. Candidates have been campaigning on the need to establish more checks and balances in the system to avoid an institutional crisis such as the one that shook the country a month before the vote.

“One of the main subjects is about how to reform the institutions, and how to move beyond an exacerbated presidentialism,” said Alioune Tine, a political analyst and founder of the think tank AfrikaJom Center.

“The power is too concentrated in the hands of the president and this can cause institutional crises,” he added.

![Voters in Senegal will cast their ballot on March 24 after weeks of turmoil due to President Macky Sall's attempt to postpone the elections [John Wessels/AFP]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/AFP__20240302__34KN467__v1__Preview__SenegalPoliticsElectionProtest-1710323923.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C514)

What is the state of the country on the eve of the elections?

Sall can bank on economic success. The country has witnessed an average 5 percent growth for the past 10 years – before a stall due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

But before that, foreign direct investment in the country grew steadily, hitting nearly $2.6bn in 2021, an eightfold increase compared with 10 years earlier. The country was also in the middle of major reforms under a $1.9bn International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan last year and new natural gas projects are expected to take Senegal’s growth rate to double digits by 2025, according to the IMF.

Sall has also made Senegal attractive to investors by being a vocal critic of the military coups that have rocked the region. Since 2020, power grabs have taken place in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger.

But those successes have been eroded as Sunday’s vote comes on the back of years of domestic political turmoil that have tarnished his image.

The past three years were marked by deadly protests, internet shutdowns and human rights regression, rights groups say. Since 2021, at least 40 people have been killed in violent clashes and authorities have arrested up to 1,000 opposition members, according to Human Rights Watch.

Following his failed election delay, Sall appeared to soften his tone in a move many consider a way to make a clean exit. He allowed protests to take place and introduced a controversial amnesty law to release hundreds of political prisoners.

Discussion about this post