By THE NEW YORK TIMES

Neo Lu had been looking forward to starting his lucrative new job as a translator. But from the moment he arrived, he knew something was off.

He hadn’t been hired. He had been kidnapped and forced to work for an abusive online scam operation. Only by understanding how it worked could he hope to escape.

He had been promised a generous salary. A better work-life balance. A chance to live in the vibrant metropolis of Bangkok. His fluency in English would be put to good use as a translator for an e-commerce company, the recruiter had said.

More than anything else, Neo Lu, a 28-year-old Chinese office worker, believed the gig would be the new start he needed to save money for his dream of emigrating to the West. So in June of last year, he said his goodbyes, flew to Thailand and headed for his new job.

But when he arrived, his head was spinning from the scorching sun — and the feeling that something was very wrong. Instead of an office building in a city, Mr. Lu had been dumped at what looked like a labor camp haphazardly built on a patch of jungle and muddy fields.

Within the compound were spartan, low-rise concrete buildings with barred windows and doors. Two men in combat fatigues, carrying rifles, guarded the main entrance. High walls and fences topped with razor wire surrounded the compound, clearly meant to keep not only outsiders at bay, but also those inside from leaving.

As Mr. Lu quickly realized, there was, in fact, no translation job. No e-commerce company, either. It had all been part of a ruse, starting with a posting on a Chinese job forum, perfected by human traffickers to get people like him to travel to Thailand.

The traffickers had led Mr. Lu across the Moei River, a muddy waterway on Thailand’s porous border, and smuggled him, without his knowledge, into a remote corner of Myanmar. There, they handed him over to a Chinese gang that had paid for him.

Mr. Lu had essentially been abducted and sold into a criminal enterprise, far away from everything he knew.

That was how he became one of hundreds of thousands of people who have been trafficked into criminal gangs and trapped in what one research group has called a “criminal cancer” of exploitation, violence and fraud that has taken root in Southeast Asia’s poorest nations.

Mr. Lu, who goes by the nickname Neo for the character in the Matrix movies, spoke to The New York Times on the condition that his full name not be used, for fear of retribution from the criminals. The Times verified the details of his travel, captivity and eventual rescue by interviewing his parents and two friends, as well as by reviewing text messages, copies of travel documents and letters issued by Chinese authorities.

His account of being trafficked aligns with those of many others who have been rescued from such camps. Taken together, his experience and the material he was able to smuggle out are a rare window into the inner workings and tactics of an underworld that is operating on a staggering scale.

From bases in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, the gangs coerce their captives into carrying out complicated online scams that prey on the lonely and vulnerable around the world. Typically, such hoaxes involve using fake online identities to draw people into fictitious romantic relationships, then tricking them into handing over large sums of money in bogus cryptocurrency schemes.

The scam is known as “pig butchering,” for the process involved in gaining the trust of its targets, which can take weeks — fattening up the pig, so to speak — before going in for the kill.

Many of the people who have been abducted and forced to work for the scam gangs are Chinese, because the groups initially focused on stealing from people in China. But the gangs’ targets have expanded internationally. In the United States, the F.B.I. reported that in 2022, Americans lost more than $2 billion to “pig butchering” and other investment scams. Increasingly, people from India, the Philippines and more than a dozen other countries have also been trafficked to work for scam gangs, prompting Interpol to declare the trend a global security threat.

The criminal groups try to break their captives with a mix of violence and twisted logic. Those who disobey are beaten. Once they start working, the victims are often led to believe that they have become complicit in the crime and would face jail time if they returned to their countries. The gangs often take away the abductees’ passports and let their visas expire, creating immigration complications.

The operation that held Mr. Lu paid workers a small cut of the profits to spend on the food, gambling, drugs and sex that served as the site’s few distractions from working in sweatshop conditions. Some gangs rewarded workers with more money or the possibility of getting travel documents to leave.

“The scam groups need to give trafficking victims the illusion that they could work their way out of this system,” Mr. Lu said. “Eventually the donkey goes from trying to avoid getting whipped to chasing after the carrot dangled in front of them.”

Mr. Lu said he pleaded to be freed, but his captors refused. They put him to work as an accountant, and over months he tracked millions of dollars in illicit income and managed their day-to-day expenses.

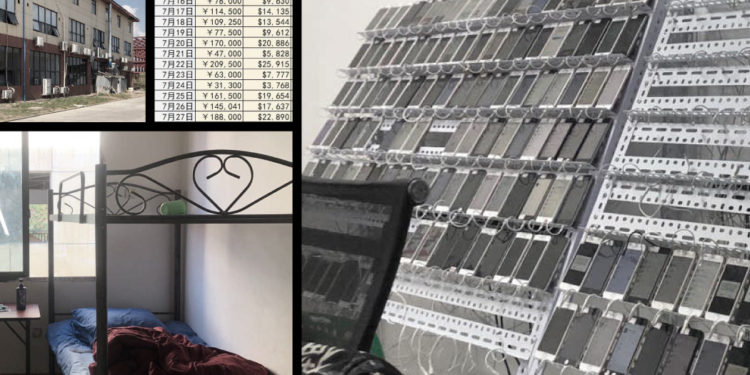

A spreadsheet tracking operating expenses and scam revenue for Nov. 2022, created by Neo Lu when he worked as the scam operation’s accountant.

While he was still inside the camp, Mr. Lu contacted The New York Times. He sent hundreds of pages of financial records and photos and videos of the site, hoping to expose the operation at some point.

Mr. Lu also sent a map screenshot that approximated his location in Myanmar. The Times analyzed satellite images of the area and geolocated the photographs Mr. Lu took on the ground to a known scam compound called Dongmei Zone.

Then, in January, he went silent.

Arriving in ‘Little China’

Myawaddy, in southeastern Myanmar, where Dongmei Zone is, offers the perfect base for scam groups like the one that had abducted Mr. Lu.

There, the government is powerless. Thugs rule with virtual impunity, backed by the local ethnic armed groups that they pay for security. Such conditions have made the area a magnet for Chinese crime gangs, leading to a mushrooming of illicit casino enclaves and a surge in drug trafficking and money laundering.

U.S. authorities say that a key investor in the Dongmei Zone is Wan Kuok Koi, a convicted Chinese organized crime figure also known as “Broken Tooth.” Mr. Wan could not be reached for comment.

More than a dozen similar illicit developments run by Chinese scam gangs sprang up in Myawaddy around the same time as Dongmei Zone, according to estimates by the United States Institute of Peace, a research group based in Washington.

Once people like Mr. Lu have been spirited into Myanmar, they are cut off from their families and friends, in a region mostly off-limits to foreigners and the media, and far from the reach of the police.

Mr. Lu called Myawaddy “Little China.”

Dongmei Zone, which houses online scam operations, was built between Feb. 2020 and Feb. 2022 in an area along the Thailand-Myanmar border.

Source: Maxar Technologies

In some ways, Dongmei reminded him of a Chinese factory. Workers had access to a canteen, a convenience store that sold Chinese products, a Chinese restaurant, a small casino called the Golden Horse and a karaoke bar.

But it was clearly organized around illicit activity. Methamphetamine, MDMA (also known as Ecstasy) and ketamine were available for purchase in the arcade and karaoke bar, Mr. Lu said, and one of the compound’s dormitory-like buildings also doubled as a brothel.

Security was tight, especially around the perimeter. Guards posted in watchtowers and at the gates prevented workers from escaping. The Moei River surrounded much of Dongmei.

The view from Neo Lu’s window in one of the buildings rented by the scam operation.

The head of the organization was a gray-haired, middle-aged Chinese man with bulging eyes whom everyone called Xi Ge, in Chinese, which roughly translates as Brother Joy. No one in the camp used their real names.

Mr. Lu said Xi Ge rented the space from the Dongmei compound and ran an operation of about 70 people, most of whom were Chinese nationals who were also trapped in Myawaddy. Mr. Lu was later told that Xi Ge had paid human traffickers $30,000 for him.

Because its targets were mostly in China, the group set all the clocks ahead by an hour and a half, to conform with Beijing time. The days were long and grueling: work started at 10:30 a.m. and ended at midnight, with three breaks of only a half-hour each. Workers had just one day off each month.

They sat in an open office under the close watch of supervisors. In one room, workers used hundreds of cellphones that lined the walls to build authentic-looking profiles on WeChat, a popular Chinese chat app. Such profiles were fed with data, including stolen WeChat accounts, cell phone numbers, photos and videos, that was often purchased wholesale online.

The workers spent their days using the WeChat accounts, swiping over social media feeds on each device to mimic normal use and get past the app’s fraud detection system.

Photos and videos of the scam operation’s account farm, its main office space and a partially occupied dorm room, taken by Neo Lu in secret.

Mr. Lu slept in a room that was infested with earwigs and reeked of sewage gas. He shared it with seven other Chinese men.

Lying in bed, Mr. Lu would wonder how he had strayed so far from the life he once thought he would have.

He had studied engineering at a university in Britain for a year when he was 17, but his parents, who run a small business in eastern China, had to pull him out because of the cost. He had become depressed, then restless. In the years since then, he had worked for Chinese firms in Oman, Nigeria and Kenya, but he yearned to save enough money to pay his own way through college and eventually move to the West. In his mind, that single-minded ambition was what landed him in Myanmar.

Now, he was focused on how he would escape. He knew he needed to get help, but his phone had been confiscated by his supervisor when he arrived at the camp. During his first week, he used a work phone to reach out to a friend on Telegram, the messaging app.

The next day, managers confronted him, threatening to beat him or sell him to another compound in Myawaddy rumored to harvest the organs of trafficked workers.

Mr. Lu broke down and begged to be released. “I can’t do this. I’m not cut out for this. Please let me go,” he recalled telling his captors.

It didn’t work.

Xi Ge eventually presented Mr. Lu with three options: pay a ransom of $30,000, work as a scammer like everyone else, or put his skills to use and help with accounting. After six months, he said, the gang would consider releasing him.

Mr. Lu went with the accounting option.

Mr. Lu booked such expenses as electricity bills, office rent and commissions. But other payments that he tracked were unique to the criminal business. “Tea fees” referred to money paid to brokers to be connected with a human trafficker. “River crossing fees” covered the cost of smuggling workers over the border. “Soldier fees” were payments for armed guards to escort people in and out of the compound. “Caravan fees” were funds for laundering money.

How the Hoax Worked

Xi Ge’s organization focused on trying to defraud Chinese-speaking women between the ages of 30 and 50, preferably married. One team was in charge of buying personal data in bulk and identifying potential victims. Another team sent out unsolicited friend requests and messages to those targets on WeChat.

From there, the workers followed a pre-written script, according to Mr. Lu. Here’s how it played out:

Xi Ge’s group targeted married women because they were likely to go to great lengths to avoid asking their families for help or reporting the fraud to the police, out of fear of being accused of infidelity, Mr. Lu said.

The operation raked in money at a rate that surprised Mr. Lu. In the five months between July and November, the group had taken more than $4.4 million from 214 victims, according to the records he kept.

The files Mr. Lu kept also included the contact numbers of some of the victims. The Times called more than a dozen women who had been defrauded by the group. One woman who spoke on condition of anonymity said she had lost more than $15,000 in November of last year. Another woman, who wanted to be identified only by her first name, Yi, said she had been duped out of $35,000 last August, including money she had borrowed and was still trying to pay off.

The internet giant Tencent, which owns WeChat, said in a statement that it prohibited criminal behavior on the platform and worked to fight scams. It also urged users to be vigilant.

Punishment and Confinement

After nearly six months, Mr. Lu had gained the trust of his captors, who allowed him to use his personal cell phone for a few minutes a day.

He contacted his family and friends and told them he had been kidnapped. He took photos of the compound and filmed short video clips inside the group’s main office, taking pains to avoid being noticed. He drew an organizational chart and wrote a glossary of industry terminology. He uploaded everything onto an encrypted email account and deleted the files from his work devices.

He then sent the material, along with the financial records he had kept from July to November and a list of the scam victims’ legal names, transaction records and phone numbers, to The Times.

On Jan. 3, Mr. Lu begged Xi Ge to keep his promise to release him. Instead, he was taken to a dorm room reserved for punishing disobedient workers.

Mr. Lu was handcuffed to a bunk bed, released only for meals and bathroom breaks. A guard watched him at all times. Mr. Lu’s electronic devices were taken from him. He told his captors that he had reached out to the media and friends.

“I tried to get them to understand that I had gotten myself and them cornered,” he recounted. “They could no longer trust me or resell me to another organization. I was a ticking bomb.”

That was when the torture began.

A man he knew only as Ah Hong, who handled logistics at the compound, slapped and punched Mr. Lu. He beat him with a hollow PVC pipe. He shocked him with a stun gun baton. The pain was excruciating.

Ah Hong told him he would continue to be punished until he stopped asking to leave. In between beatings, senior leaders took turns trying to persuade Mr. Lu to give up. They promised to let him lead a new branch of the operation focused on English-speaking victims, a position that would be more lucrative.

Mr. Lu refused and said his family would pay a ransom.

One day, Ah Hong walked in, his face concealed with a gray scarf. He set up a camera in the room, as a group gathered to watch.

He hit “record,” then took out the stun gun. He was making a ransom video.

Still frames from a ransom video sent to Neo Lu’s parents in China.

On Jan. 14, more than 2,000 miles away from Mr. Lu, in the Chinese city of Taizhou, Mr. Lu’s parents’ phones lit up. The gang had sent two video clips.

Mr. Lu could be seen sitting cross-legged on the floor between two bunk beds, his hands cuffed behind his back. A man standing above Mr. Lu held a stun gun on him, the jolts of electricity setting off loud crackling and blue sparks. He went for Mr. Lu’s right knee, then his left knee, abdomen and back.

Mr. Lu writhed on the floor, howling in agony, in one of the clips.

For his parents, it was too much to bear.

“My husband wouldn’t let me, but he watched it,” said Mr. Lu’s mother, Ms. Peng, who spoke on condition that her first name not be used. “My heart could not take it.”

The Rescue

The gang demanded 500,000 Chinese yuan, or about $70,000. For Mr. Lu’s parents, who ran a small business selling banners and LED signs, this was no small sum.

Ms. Peng responded to Xi Ge, asking for more time and information. How should they pay the ransom? Whom would they send the money to? She added: “Let us see him one more time.”

Mr. Lu’s parents reported the kidnapping to the police and sought help from Chinese embassies and business associations. They also implored a higher power: every morning at dawn, Ms. Peng and her husband went to the beach to pray for their son’s safe return.

Then the police in their home province of Zhejiang introduced them to a man they said could help.

He went by the nickname “Dragon” and said he had successfully rescued more than 200 Chinese nationals from scam compounds in Southeast Asia. He also kept a blog about his experiences.

Dragon called the couple and explained to them in chilling detail what would likely happen next. Mr. Lu’s captors, he said, would continue to send them gruesome images and videos. If they paid the ransom, though, the extortion would never end.

Instead, he said, they should stall and appear cooperative. He would find another way.

On Jan. 21, a week after the ransom videos had been sent, Dragon told Mr. Lu’s parents that a powerful friend of his, a Chinese businessman with connections to the local armed militia, had made a trip to Dongmei earlier that day and confirmed Mr. Lu was there. Dragon said his friend could get Mr. Lu out in two days.

Ms. Peng connected The Times with Dragon, who corroborated the timeline and described the rescue in general terms. Dragon spoke on condition of anonymity and declined to provide specifics out of concern that going public would jeopardize future rescues.

Dragon said that the well-connected Chinese businessman went to Dongmei again on Jan. 23, this time flanked by a general and dozens of armed soldiers from the Border Guard Forces, a local armed group aligned with the junta that rules Myanmar. He asked for Mr. Lu.

Experts say that local militia groups often have relationships with the owners of such compounds, but are also obliged to keep the criminal groups that operate in the compounds in check. Dragon said that Xi Ge had crossed a line by drawing the attention of the Chinese authorities with the videos of Mr. Lu being tortured. That was how Dragon’s associate, the businessman, was able to get the general to intervene in Mr. Lu’s case, Dragon said.

The Times could not independently verify the details of the rescue.

Mr. Lu, who would be held in the room for 18 days in total, was unaware of the negotiations. One day, he was suddenly told to change and get into a golf cart.

Just like that, Mr. Lu was out.

He said the local militia questioned him and took his phone, laptop, IDs and cash. Within days, he was back in China; his flight landed in Shanghai on Feb. 2.

His mother had packed a thick winter jacket for him, knowing that coming from Southeast Asia, he would not be dressed for the bracing cold. When she saw her son emerge from the arrivals area, a flood of relief washed over her.

Mr. Lu hugged his parents, who were both overcome with tears.

Though the family had avoided paying a ransom to the gang, Ms. Peng said that she had sent about $37,000 to Dragon, money he said would go to his associate and the general for their help.

The next day, Mr. Lu went to the Chinese police, handing over all the materials he had collected and offering detailed explanations of the scam operation as he knew it. In a statement seen by The Times, the police wrote that the authorities had helped rescue Mr. Lu from a scam camp in Myanmar, and that he “had no prior engagement in activities such as online gambling and online scamming.”

In recent months, Chinese authorities have been working with Southeast Asian officials to arrest and deport to China thousands of people accused of working in scam groups, but experts believe many organizations have simply relocated their operations.

Mr. Lu remembers that one of his captors had told him to keep his mouth shut after getting out. But Mr. Lu has other plans. He has spoken to the Chinese media and consulted on a movie project, and he plans to write a memoir.

“These Chinese gangs are spreading a form of modern slavery,” Mr. Lu said. “I want the whole world to know.”

Adriana Loureiro Fernandez for The New York Times

Discussion about this post