KIGALI, Aug 23 2024 (IPS) – In Kubewo village in eastern Uganda, children often go to work with their parents in the coffee gardens. Earnings from Arabica coffee are used, their parents and grandparents say, to pay for children’s education and other expenses for the family.

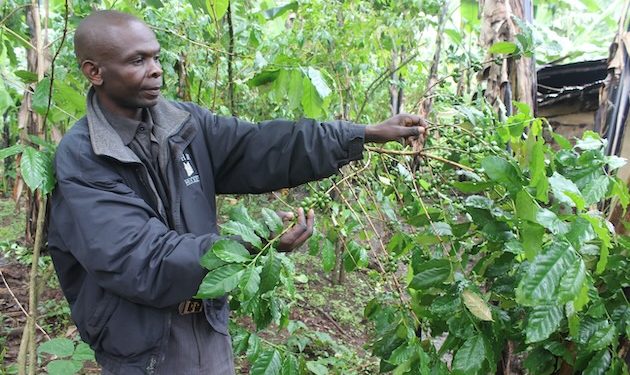

Farming families justify the labour, saying that children are observing adults and learning from their examples. Children lend a hand in harvesting coffee and ferrying it back home.

The Global Fund to End Child Modern Slavery’s 2022 report, titled Child Labor in the Coffee Industry in Eastern Uganda, found that the overall prevalence of child labour in the coffee supply chain was 48 percent—51 percent among boys and 42 percent among girls.

“The nature (activities) and extent (regularity of participation) vary depending on the stage in the supply chain and season. Boys, more than girls, participated in more physically demanding activities such as spraying, pruning, carrying, and loading and offloading coffee,” the report said, adding that a key driver of child labour was systemic poverty.

For farmers, new European Union regulations mean that this practice will have to change. In April 2024, the European Union adopted the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. It requires companies operating in the EU to consider child labour as a critical adverse impact that has to be addressed if it happens in a coffee value chain.

One of the regulatory indicators is that “child labour is not present and the employment of young workers is responsibly managed. Child labour is eliminated and children are protected. Where young workers are employed, their employment follows best practices.”

Uganda is one of the coffee-producing countries that has started taking steps to comply with a related regulation, the European Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), which will outlaw sales of products such as coffee beginning on December 30, 2024, if the coffee is linked to deforestation.

The country recently reviewed its coffee laws to provide for the registration and regulation of coffee value chain actors. In collaboration with partner organizations and the government, farmers are registered to geo-reference their gardens before December 2024. The system will enable the ‘last-mile tracing’ of coffee farmers.

“The biggest focus for us to be compliant with EUDR and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) is this traceability system. The other critical issue is the sensitisation of the coffee actors,” said Gerald Kyalo, Director of Development Services at the Uganda Coffee Development Authority.

The system will cost Uganda an equivalent of USD 9 million.

In April this year, Reuters reported that the EU had given Uganda a 40 million euro (USD 43 million) grant to help Africa’s largest coffee exporter comply with the new EU policy that bars imports of commodities whose production resulted from forest destruction.

Kyalo told IPS that child labour in the coffee sector is complex, as it is in other coffee-producing countries.

“Labour takes maybe 50 percent of inputs in terms of funds. Therefore, family labour is always relied on and in most cases, it is children. Its parents are working with children, so it is a complex value chain,” said Kyalo.

“There is a thin line between child labour and what people call training their children. This needs to be tackled and sensitisation can help us.”

George Namatati, a 74-year-old peasant coffee farmer, is worried that the old systems of growing coffee using family child labour are about to collapse. He told IPS that he heard over the radio that the government would fine and jail farmers found working with children in coffee gardens.

Namatati is bitter that his government has adopted these sweeping changes.

“They are completely changing the way we farm in this area. You cannot fine me because I am working with my grandchildren. That is how we have (always) cultivated this crop,” he said.

Mathias Nabutele, the chairperson and founder of the Coffee a Cup Cooperative Society, told IPS that the EUDR would change the conversation about coffee farming. Rather than change the practice, he suggested that perhaps farmers would look for new markets.

Nabutele and other coffee farmers based in the Mount Elgon area in Eastern Uganda have been promoting local consumption of Arabica coffee. He said that under the new conditions, farmers need to explore alternative markets for coffee.

“Then what are those alternative markets and what are their requirements? Because this is a very competitive world. We are also promoting domestic consumption.”

But he acknowledges that EU member countries are destinations for over 60 percent of the coffee produced in Uganda.

“For the government and players in the coffee sector, they cannot afford to lose out on this very important market.”

But farmer Namatati said the EU should rethink some of its policies that they keep “pushing down the throats of coffee farmers.” He revealed that more young people are moving away from coffee farming. He explained to IPS that there is a risk of losing valuable knowledge, skills, and experience if it is not effectively passed down to successive generations.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines child labourers as those who “are those entering the labour market, or those taking on too much work and too many duties at too early an age.” It includes labour that affects the child’s access to education and play.

Rosalind Kainyah, advisor and speaker on sustainability and responsible business in Africa, writes, “The EU’s impending regulations on forced labour, which include child labour, could place some African businesses that export to the EU in a sticky mix of law, culture, and human rights.”

While she condemned the “worst forms of child labour,” saying they require urgent action, a policy position that focuses on harmful child labour rather than a blanket ban would be more productive. Instead of a complete “zero-tolerance” approach, “EU policymakers should develop a contextually sensitive understanding of child labour,” she suggests, saying it is important to “understand family reliance on child labour.”

“The African Union, for example, prevents work that interferes with children’s development, but unlike the UN and the International Labour Organization (ILO), the African Union also recognises that ‘every child shall have responsibilities towards their family and society’,” Kainyah writes.

Some experts have indicated that household poverty and economic vulnerability are some of the underlying root causes of child labour in coffee value chains all over the world.

Kenneth Barigye, the Chief Executive Officer of Mountain Harvest Uganda, suggests the need to sensitise the farmers to protect their children.

“I am a parent. We all wish the best for the kids but this situation limits us. The average age of a farmer in Uganda is about 63. So chances are that this old man or woman is living with grandchildren whose parents moved to town but, because of unemployment, sent the kids home,” said Barigye, whose organisation seeks to build sustainable coffee value chains in Uganda.

Barigye told IPS that the cost of producing coffee in Uganda is very high and that the biggest driver of the cost of production is labour.

“As long as the farmers are earning less than production costs, they have to keep trying to figure out how to reduce the cost of production, so they will go with the child to the garden,” said Barigye.

Like Namatati, Barigye said it is from an ageing farmer that the young farmer can learn skills and agronomic coffee practices because no school trains young people in a country where agricultural extension services are lacking or are very limited.

“Eighty percent are employed in agriculture. Nevertheless, there is no formal school that trains farmers. The successful smallholder learned from their grandparents and parents. For them, it is training—it is mentorship of their children,” explained Barigye, whose organisation works with 1700 coffee farmers in Uganda.

He suggests that a farmer should be running a profitable business for them to generate enough money to take care of their family.

At the launch of the “Ending Child Labour in Supply Chains (CLEAR Supply Chains)” project in June this year, Wouter Cools, Project Manager Ending Child Labour in Supply Chains for the ILO, said an integrated approach to addressing child labour in supply chains was needed, involving multiple stakeholders, including UN agencies like United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), civil society, governments and the private sector.

While human rights groups welcome the EU directive, saying it will address environmental and social sustainability, small-scale coffee farmers fear they are about to suffer due to the vagaries of global trade.

Pison Kukundakwe, a coffee farmer cooperative representative, was among the farmers chosen to travel to the EU headquarters in Brussels when the regulations were under consideration.

He told IPS that there is a need to change from the current system that dictates that coffee farmers are price takers and not determinants.

Coffee is a critical part of Uganda’s economy. Over 1.8 million households grow coffee, and coffee contributes nearly a third of the country’s export earnings, paying for critical infrastructure like roads, hospitals, and schools.

In 2023/24, coffee exports were 6.13 million bags valued at USD 1.144 billion. This was an increase of 6.33 percent in volume and 35.29 percent in value compared to FY 2022/23, when exports were 5.8 million bags valued at USD 846 million.

Coffee is produced in diversified systems on small pieces of land with very low input use. The average coffee plot size is 0.23 ha, and 90 percent of farmers own plots of less than 0.5 ha.

“You see people working hard to produce coffee. Farmers are at the mercy of the ups and downs of the commodity. What they go through to bring coffee from the farm is never thought about,” explained Kukundakwe.

Discussion about this post