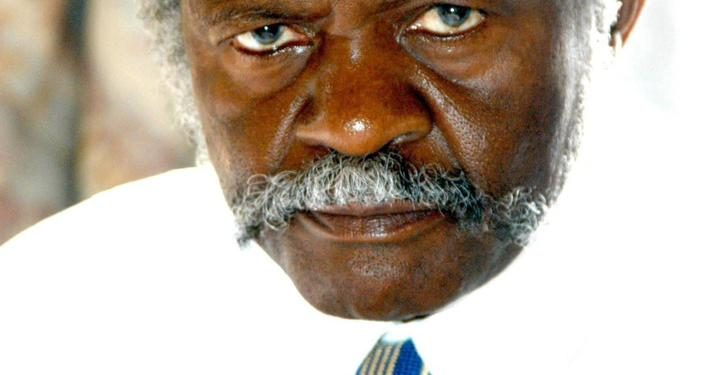

He was undoubtedly a legendary figure. In the 1950s, Jehoash Mayanja Nkangi made history as the first Ugandan to study at Britain’s prestigious Oxford University. He was also one of the first Black lecturers at Lancaster University. Additionally, he served as Buganda’s youngest Katikiro and held diverse roles in various governments, including the present NRM administration.

Mr. Nkangi was a living chronicle of history. During a visit from our reporter, Rtn. Robert Walakira, Mr. Nkangi openly recounted his remarkable life story just a few weeks before his passing. Below are excerpts from the interview.

QN: Owekitiibwa, nearly half of Uganda’s population is under 18, and many people are unaware of who Mayanja Nkangi is or his contributions to our nation’s journey toward independence. If you wouldn’t mind, could you share your life story with us, please?

Mayanja Nkangi: Before I answer your questions, I want to know whether your readers are interested in my life and the future of Africa. I don’t want to be irrelevant.

Reporter: That’s why we are here, Owekitiibwa.

Mayanja Nkangi: If you say so.

QN: Great. I would like to start by asking: when did you join politics?

Mayanja Nkangi: To answer your question, I joined politics in 1948, likely before your parents were born.

QN: Indeed. If I may ask, who inspired you to join?

Mayanja Nkangi: Mr. Apollo Kironde, a historian and teacher at King’s College Budo, taught us about the 1900 Buganda Agreement. I realized that it was inequitable to be ruled by European immigrants. That is when I joined politics, and that is how the anti-colonialism movement started in Uganda.

QN: Did you know Dr. Obote at the time?

Mayanja Nkangi: At that time, no. He was ahead of me. When he was at Makerere, I was still at King’s College Budo. I joined Makerere in 1950.

QN: What major did you choose at Makerere?

Mayanja Nkangi: I studied Mathematics and Applied Economics.

QN: In 1953, Sir Andrew Cohen exiled Kabaka Mutesa. What exactly caused the expulsion, and how was the status quo in Buganda at the time?

Mayanja Nkangi: It was horrifying. Cohen, a foreigner, exiling our Kabaka? Many called it a coup d’etat. It all started when the Secretary of State for the Colonies floated a new idea of a Federation for East Africa in a speech he delivered in June 1953. His speech received strong protests from Buganda, and this was when the spirit of rebellion started to grow against British rule.

It was around this time that Ignatius Musaazi had started the Uganda National Congress. We passed a resolution of disapproval and drafted a memorandum suggesting what should be done.

QN: Who were you collaborating with?

Mayanja Nkangi: During my stay at Makerere’s Northcote Hall, Abu Mayanja was my close friend. Together with four of our Northcote peers, we drafted a memorandum asking for Buganda to be granted a constitutional monarchy because Buganda was an independent state well before the Europeans arrived.

Businesspersons in Katwe rallied behind us, and as a result, Sir Keith Hancock, an Australian professor working on Her Majesty’s instructions, was sent to study the situation on the ground. This is how the 1955 agreement came about, which saw the return of the Kabaka. On October 8, 1962, Buganda got her autonomy. Other kingdoms like Ankole, Busoga, Bunyoro, and the Kingdom of Toro were all semi-autonomous.

QN: How did you end up in Britain?

Mayanja Nkangi: I joined Oxford University on a government scholarship in 1954 to study Economics, Taxation, and Public Banking. After completing in 1957, I realized that I did not want to work in the public service. So, I told the lecturer who was looking after scholarship holders to get me another scholarship so that I could study law.

In his letter to the government of Uganda, he wrote, ‘This young man has scathing intelligence, give him another three years’. I was flattered. But the Brits were not keen on the idea because, in 1957, Ghana became independent, and it was the lawyers who spearheaded her independence. So, the Brits were not ardent about law scholars. Nevertheless, I was given another three-year scholarship to study law at Lincoln’s Inn of Court in London, but I did it in one year because I was sick of the place.

QN: Were you one of the first Ugandans to study at Oxford?

Mayanja Nkangi: Yes!

QN: As we speak today, getting into Oxford is not easy for African students. I am sure it was even harder 60 years ago. Don’t you consider yourself lucky?

Mayanja Nkangi: I give glory to God. You see, even at that time, it would take much for an Englishman to get into Oxford University, but I got in there easily.

QN: As a Black student of slim build, did you experience any bullying from the white boys at Oxford?

Mayanja Nkangi: Nope. They were very friendly. They used to invite me to their homes for dinner. I remember one incident, however, when a fellow student asked me if I would consider marrying a White girl. I gave him a look, and the young man later apologized.

QN: Were you offended?

Mayanja Nkangi: I didn’t like it. Asking a Muganda to marry an English girl was an insult!

QN: Observably, there were no Baganda girls at Oxford. Are you implying that you never dated during the years you spent at this establishment?

Mayanja Nkangi: Dating is just playing about, but I can never … (long pause) let me tell you why! I think there is a reason why God created me as an African. I am not implying that He did not create them, but I am saying He created varieties for good reasons, and we should persist. (Laughter)

QN: When did you return to Uganda?

Mayanja Nkangi: 1959.

QN: What job did you do on your return?

Mayanja Nkangi: I tried to open up a law firm, but the regulations at the time were that one could not come out of university and open a law firm unless they had been at a senior lawyer’s firm for at least six months. So, I joined Benedicto Kiwanuka and Lawrence Ssebalu Advocates. These were DP diehards.

QN: Did you find the situation any better than the way you left it?

Mayanja Nkangi: Uganda was hot politically, with many political parties emerging. Three months after my return, I started my own political party, which I called the Uganda National Party (UNP). During that time, there was a boycott by traders buying Asian goods. They used to chuck them in the streets. Many were arrested, and I successfully defended them.

QN: Were you in touch with other Pan-Africans like Robert Mugabe, Oliver Tambo, or Julius Nyerere?

Mayanja Nkangi: I was not. My main interest as a Ugandan was to force the British out. The UNP slogan was, “Let us make our own mistakes.” And that chance came on 9th October 1962.

QN: How did you become a minister?

Mayanja Nkangi: After independence, I was among the 21 members nominated by Mr. William Kalema to represent Kabaka Yekka in the National Assembly (NA). At the NA, I was appointed the Parliamentary Secretary in the Ministry of Public Affairs and then a Minister without Portfolio. In 1963, I was appointed the Minister of Commerce.

QN: And how did you become the Katikiro?

Mayanja Nkangi: At 33 years old, it was very easy. Let me tell you how. There was a referendum, which saw Buganda lose the counties of Buyaga and Bugangaizi. After the defeat, Buganda Katikiro Michael Kintu was dropped. God has always been there for me.

After the referendum, the Kabaka Yekka and UPC alliance collapsed. UPC and the party I was chairing (UNP) were big rivals, but surprisingly, Obote campaigned for me because he thought it would be easier to deal with a 33-year-old Katikiro than the much-revered Masembe Kabali and Eldard Mulira, who were the two main front-runners for the Katikiroship.

QN: How did the 33-year-old Nkangi conduct his campaign against the two favored front-runners?

Mayanja Nkangi: One Sunday, someone rang to say that the Baganda wanted me to become the Katikiro. I asked him why me when there were many bigger shots? The following Monday, an old man called Ali Kasirye came to my chambers, stood in the doorway, and said, “Mayanja, I am told you are chickening out to become our Katikiro.” I told Ali that I am not chickening out, but I am not campaigning either. ‘If you can run the campaign for me, I am up for it.’ He volunteered to start my campaigns.

However, I understand when Katikiro Michael Kintu was about to be relieved of his duties, the Kabaka asked him if he could recommend anybody for the post. Kintu forwarded my name as his choice but also wondered if I would be accepted because I was only 33 and not married. When the Kabaka heard this, he shrugged it off by saying, “When I became the Kabaka, I was not married either!”

QN: At that time, were you close to the Kabaka?

Mayanja Nkangi: I would say no, and I will tell you why! In 1938, when I was a small boy, much smaller than I am nowadays, the Kabaka came to my village, and I stretched my arms thinking that he might touch me. He did not. Later, I learned that the Kabaka does not shake hands.

The second time I got close to meeting him was in 1954 while I was studying at Oxford, and he was in exile. He had come to the University to visit Ernest Ssempembwa, who was teaching Luganda at the institution.

QN: When did the problems start with Obote, yet he campaigned for you?

Mayanja Nkangi: It all started in 1966 when Daudi Ochieng (a member of Kabaka Yekka) came to Butikkilo and reported that Idi Amin and Obote had a lot of money in their bank accounts. We all wondered where they got the funds from.

The motion was tabled to investigate them on Friday, but the following Monday Obote altered the constitution and made himself the President.

The Lukiiko passed a resolution that Obote’s actions were illegal and ordered him to remove his government from Buganda soil. On hearing this, Obote invited me to his office, but I declined and informed the Kabaka about it. Had I honored the invitation, the Baganda would have called me a traitor.

QN: Where was the Kabaka at that time?

Mayanja Nkangi: He was a prisoner in his palace. He had been ousted.

QN: Are you saying that Obote outsmarted the elite Baganda?

Mayanja Nkangi: Yes, he did. You see, Baganda don’t tell lies. When I say you are a fool, you are a fool. Obote, however, played amoebic politics.

In 1962 Obote asked Grace Ibingira, Abu Mayanja, and Balaki Kirya to help him convince the Kabaka to be part of his government. You know what he said after changing the constitution? ‘I planned to destroy Muteesa for four years and when I saw him taking an oath in 1962, I knew I had got him.’

QN: You had a learned team you were working with and yourself as an Oxonian; didn’t you see this coming?

Mayanja Nkangi: You know! What you fear you hate, and what you hate you want to destroy. Obote feared Buganda. He wondered why the Kabaka and his Katikiro were cheered everywhere, yet he didn’t get anything of the sort. Let me give you an example. One afternoon, I went to a packed Nakivubo Stadium, where Obote was presiding over a football match between the Ugandan Cranes and an Egyptian national team.

I arrived slightly late at the time when Obote was inspecting the teams. When people saw my vehicle, bearing the Buganda flag, they gave a massive round of applause, distracting Obote’s inspection. I told the driver to stop the automobile and wait until the inspection was done. As soon as Obote took a seat in the pavilion, I drove into the parking yard to a boisterous acclamation. The Egyptians could not understand why a simple Katikiro could steal the show from the country’s Prime Minister. Later, Obote’s cousin, Nekyon, said, “When the Baganda see Mayanja Nkangi, they think Jesus Christ has come back!”

QN: When did you go into exile?

Mayanja Nkangi: In 1966.

QN: Did you go with the Kabaka?

Mayanja Nkangi: No. He went through Burundi, and I went through Kenya. But we linked up while in England.

QN: During your London days, did you share accommodation with Kabaka Muteesa?

Mayanja Nkangi: No. In Buganda customs, the King and the Katikiro cannot sleep under the same roof.

QN: Did the British government give the Kabaka any facilitation?

Mayanja Nkangi: No. Not politically nor financially. Steadfast friends paid for his upkeep.

QN: Did you ever think at any point that the Brits sided with Dr. Obote?

Mayanja Nkangi: It never crossed my mind.

QN: Who paid for Mr. Nkangi’s expenses?

Mayanja Nkangi: For the first year, I borrowed from acquaintances, but later I got a job in the Department of Economics at the University of Lancaster in 1967 until 1971 when Idi Amin toppled Obote’s government.

QN: Racism in the 60s was tumultuous. Was it easy for a Black man to get a skilled job in Britain?

Mayanja Nkangi: I tried many times without success. Whenever I mentioned what I studied and what I did before I came to Britain, they would tell me that I was overqualified!

When I applied for a job at Lancaster University, Mr. McBen, who was the head of the accounts department, tipped me that when they asked me how much money I was looking at, I should tell them to decide. This trick worked, and I got the job.

QN: So you take the honor of being the first Ugandan Nkuba Kyeyo?

Mayanja Nkangi: Possibly, yes! (Laughs) But at that time, there were no Nkuba Kyeyos like today. We were exiled professionals.

QN: While in exile, did you communicate with Obote?

Mayanja Nkangi: No! Communicate with him about what?

QN: Did he try to reach you?

Mayanja Nkangi: If he tried, he never got through the whole time.

QN: When did you decide to return to Uganda?

Mayanja Nkangi: One morning when I was at Lancaster University, I heard that the Ugandan government had been toppled. I went home and found my daughter standing in front of the television. The BBC had just confirmed that Obote had been ousted. I was keyed up, and after three weeks, I resigned from my job at Lancaster University. My boss called me a fool because he reckoned they were about to make me a senior lecturer. I did not listen to him, and I flew back.

QN: Were you not afraid to return to Uganda under Idi Amin?

Mayanja Nkangi: If you are a coward, how can you live in this world?

QN: Did you notify the President ahead of your return?

Mayanja Nkangi: No. I just bought a ticket and headed for Heathrow. However, when I arrived at Entebbe International Airport, some police officers attempted to apprehend me. I recall their commander asking them if they had secured my arrest warrant. Their illegal assignment was discontinued after that.

QN: On your return, did you ever come face to face with Idi Amin or did you ever apply for a job in his government?

Mayanja Nkangi: Nope. One day, however, President Idi Amin invited me and other Baganda to the Conference Centre. Prince Mutebi was also around. He asked in a tone, “What do the Baganda want?” Without dithering, I told him to give them their Kabaka. “But it is the same Baganda who told Obote to remove the Kabaka,” Amin answered back, pointing at some Baganda around.

QN: At any point, did you think your life was in danger during Gen. Idi Amin’s rule?

Mayanja Nkangi: I didn’t think so. However, one day, one Nanyonga who worked as a spy walked into my chambers and saw the Kabaka’s photo hanging on the wall. She asked why I didn’t have Amin’s photo in my office. I told her that Buganda was my history and she left. After a week, she came back and enquired, ‘Why don’t you become a minister?’ I told her that I was a minister before, let others get a chance to serve. And after a few days, she returned again and asked in Luganda, ‘Lwaaki Amin atta abantu?’ (Why is Amin killing people?) I asked her if she had ever been a leader and concluded by reassuring her to give him time to settle in. She never saw her again after that.

QN: Did you ever meet Dr. Obote again after 1966?

Mayanja Nkangi: No, but he used to ask people about my whereabouts. During the 1980s, Obote asked Paul Ssemwogerere, “Where is your commander?” Of course, he was asking about me. When I learned about this, I called a press conference and told journalists, ‘Today Obote is asking where Ssemwogere’s commanders are, but next time he will be asking who pulled the trigger.’ It did not take long before his government was toppled.

QN: After the 1985 military coup, you were appointed the Minister of Labour. Did you participate in bringing down Obote?

Mayanja Nkangi: Not directly. I was appointed Minister of Labour without my knowledge; I heard on the radio that I was appointed minister! I have a feeling that Paul Muwanga did it to please the Baganda.

QN: But you accepted the post nevertheless. Why?

Mayanja Nkangi: Let me tell you why! One afternoon, I was called to take an oath. I drove to the parliament building but refused to swear in! The presiding judge looked at me and said, ‘I admire your courage.’ After three days, Muwanga sent a soldier to tell me that he was waiting for me to take the oath. This time, my colleagues advised me to accept the appointment because Paul Muwanga was an autocrat who could do anything to harm me. After a few months, Tito Okello Lutwa was toppled, the NRA took over and formed a government in which I was appointed Minister of Education. In 1992, I was moved to the Ministry of Finance until 1998 when some people wanted me out.

QN: Who are these people?

Mayanja Nkangi: I won’t name them today because the Bible says, “there is a time to speak and a time to keep quiet.” Anyway, President Museveni moved me to the Justice and Constitutional Affairs Ministry. God is great. I was appointed to all these posts without lobbying! Not bad for a chap who studied on scholarships.

Mayanja Nkangi passed away from pneumonia on 6th March 2017. He was laid to rest four days later at his ancestral home in Kanyogoga village, Kalungu District. He was 86 years old.

Interviewer: Robert Walakira The Amasiro Post, RC Kasubi. Syndicated Content ©️EYECON MEDIA +447585568960 +256753975774 [email protected]

Discussion about this post