By AL JAZEERA

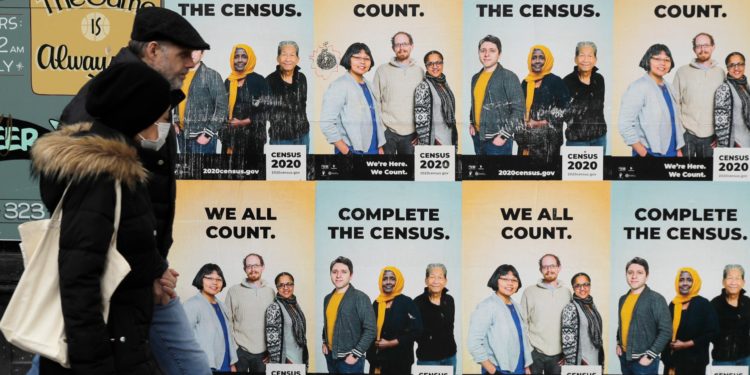

Advocates for Arab Americans routinely use one word to describe how diverse communities from the Middle East and North Africa have for decades been categorised in the United States Census: “Invisible”.

But that is set to change when the next federal census is conducted in 2030, with the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) announcing Thursday new federal standards on collecting race and ethnicity data. For the first time, Americans who trace their ancestral roots to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) will have their own category on the decennial survey.

“It’s transformative,” said Maya Berry, the executive director of the Arab American Institute (AAI), who has for years advocated for the update.

“For more than four decades, dating back to the foundation of our organisation, we have highlighted that there is no accurate count of our community because a checkbox did not exist on federal data collection forms, particularly the census,” she said.

“It’s incredibly significant and will have a very real and tangible impact on people’s lives.”

In the US, official counts of populations have wide-ranging impacts, affecting how federal dollars are disbursed to meet the needs of certain communities, how congressional districts are drawn, and how certain federal anti-discrimination and racial equity laws are enforced.

But US residents with ethnic and racial ties to MENA had previously fallen into the “white” category, although they could still write in the country with which they ethnically identify. Observers say this has long resulted in a vast undercount of the community, which can make it near impossible to conduct meaningful research on health and social trends.

Speaking to Reuters news agency on Thursday, an OMB official said the latest standards are meant to “ensure we have high-quality federal data on race and ethnicity”. That will help, the official said, in understanding various impacts on “individuals, programs and services, health outcomes, employment outcomes, educational outcomes”.

‘First step’

Abed Ayoub, executive director of The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, hailed the update as a much-needed “first step”.

“This has been a long time coming,” Ayoub told Al Jazeera. “We feel that this resets the conversation on the issue.”

“Before, we were completely ignored. We had no category. The conversation moving forward will be ‘How do we refine this category, revise this category over the years to ensure that it is a representative and fair category?’”

Changes to how such data is collected are infrequent, with the last update coming in 1997. President Barack Obama proposed new standards for the US Census’s methodology, but President Donald Trump delayed their implementation.

Beyond the census, the new standards released on Thursday also require that federal agencies submit a compliance plan within 18 months and update their surveys and administrative forms within five years. Among other measures, the new standards eliminate the use of derogatory words like “Negro” and “Far East” from federal documents.

They also combine race and ethnicity into a single category, bridging an often difficult-to-parse distinction between categorisations based on physical attributes and those based on shared language and culture.

Advocates have argued that separating the two has historically caused confusion that led to undercounts, while complicating efforts to add new categories.

The Leadership Conference Education Fund, a coalition of civil and human rights groups, has noted the separation had disproportionately affected those who identify as Latino, typically referring to ethnicities specifically from the Americas, many of whom found, as one example, the distinction between Hispanic and Latino confusing.

About 44 percent of Latinos who responded to the US Census in 2020 chose “some other race”, according to the group.

Undercounts ‘harm lives’

Like Ayoub, AAI’s Berry also noted that the reception of the new standards has been somewhat muted, saying more testing should have been conducted to refine the subcategories included in the MENA category to better reflect the US population.

She pointed to the absence of a specific subcategory for groups like Black Arabs, who hail from across the Middle East, as an example.

“Typically we would be in a place where we should just be celebrating the new category,” she said. “And regrettably … We’re having to sort of worry a bit more about how we make sure it doesn’t produce a continued undercount of our community.”

Still, Berry said, the US is a step closer to a system of data collection that reflects the country’s diversity, and that is vital.

“Governments, state governments, local authorities, everybody requires data in order to be able to do almost every single aspect of the way they provide services to citizens,” she said. “There’s literally nothing that the multitrillion-plus-dollar federal budget is not impacted by in terms of the federal data collection.”

She pointed to the COVID-19 pandemic as a perfect example of just how important it is for governments at all levels to be able to quickly identify the needs of diverse communities across the country.

“Part of how the government has to operate and inform their policy is with data about where communities are and how to best reach them,” Berry said.

“And if you’re rendered invisible on that data, you’re simply not there. Dramatic undercounts produce policies that actively harm people’s lives.”

Discussion about this post