In late October 2023, the veteran Israeli peace activist Gershon Baskin published an open letter denouncing a man he had long called a friend – Ghazi Hamad, a senior Hamas official. Baskin, an architect of the deal that freed the Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit from Hamas captivity in 2011, is one of the only Israeli citizens who has maintained consistent contact with leaders of the Palestinian Islamist movement. Hamad, a former journalist with a degree in veterinary medicine, was also involved in the Shalit negotiations and served as deputy foreign minister in the 2012 Hamas government. Prior to the 7 October attacks, for more than a decade and a half, Hamad and Baskin had exchanged frequent phone calls and text messages. These mainly concerned negotiations around prisoner swap deals, and sometimes the possibility of a long-term truce between Israel and Hamas. The pair developed a warm working relationship based on mutual trust.

After 7 October and the start of Israel’s ground invasion of the Gaza Strip, that relationship started to unravel. Hamad insisted that the attacks were entirely justified, and denied that Hamas fighters had carried out atrocities during their incursion into Israel. On 24 October, in an interview for a Lebanese TV channel, Hamad vowed that Hamas would commit the same acts “again and again”. He said that “Al-Aqsa Flood”, Hamas’s name for its armed offensive, “is just the first time, and there will be a second, a third, a fourth”. Once considered a thoughtful observer of Palestinian politics, Hamad now declared that “nobody should blame us for what we do – on 7 October, on 10 October, on October 1,000,000. Everything we do is justified.”

To Baskin, this did not sound like the man he had come to know. The proclamations by Hamad, “thought to be one of the most moderate people in Hamas”, Baskin noted, landed like a betrayal. Baskin had long argued that it was possible to broker an agreement with Hamas for a “hudna”, or a fixed-term armistice, in exchange for opening the land, air, and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip, which Israel has enforced, with Egypt’s support, since Hamas came to power in 2007. Baskin had believed that Hamad could help move Hamas toward acceding to a two-state solution. In the months before 7 October, Baskin had been trying to organise a meeting with him in Europe to discuss the prospect of a long-term truce.

But after 7 October, Baskin, too, shifted his position. “Hamas has forfeited its right to exist as a government of any territory and especially the territory next to Israel,” he wrote in an article for the Times of Israel on 28 October. “Hamas now fully deserves the determination of Israel to eliminate them as the political and military body that controls Gaza.” More recently, Baskin has proposed exiling Hamas leaders such as Yahya Sinwar from Gaza as part of a potential ceasefire deal. He has also proposed that Hamas be barred from contesting future Palestinian elections unless they renounce violence. It is not that Baskin has given up on peace – he remains a fixture in international media coverage as a lonely, even desperate Israeli voice calling for an end to the war. It is that he no longer believes Hamas can be part of the equation. Since October, many Israelis, even or perhaps especially on the centre left, have gone on a similar journey.

In late December, I sat with Baskin in the basement of his home, in a quiet, leafy neighbourhood of Jerusalem. Born in New York, Baskin is a stocky, energetic man in his late 60s. He answered the door wearing the silver dog tag engraved with the words “Bring them Home”, which has become an emblem of the movement calling for the return of the more than 100 Israeli hostages still held by Hamas.

One question looms over the story of Baskin’s exchange with Hamad: did Hamas change, or did Baskin simply misunderstand the group all along? Baskin believes it was the former. “Most of the years previous to 7 October, there was a willingness to explore pragmatic, long-term ceasefires,” he told me. “In retrospect it became clear – there were signs, but none of us read them – that from two years before 7 October, Hamas had made a decision that there was a no-go on a long-term modus vivendi [with Israel] and that they were beginning to make their plans for an eventual attack.”

Baskin recalled his final exchange with Hamad in late October. “During the early days of the war, when I heard that his house was bombed, and I didn’t know he wasn’t in Gaza, I said to him: ‘Ghazi, if they’re going after you, there is no one in Hamas who is safe.’” (Ahead of the war, Hamad had departed for Beirut.) “He responded to me: ‘We have lots of surprises, and we will kill lots of Israelis.’”

That was when Baskin posted his open letter to Hamad on social media. “I’m sorry to say that you were someone who I actually trusted and thought that we could help bring a better future to our peoples. But you and your friends have brought the Palestinian cause back 75 years,” he wrote. “I think you have lost your mind and you have lost your moral code.” And with that, Baskin severed their ties.

Five months into Israel’s brutal war in Gaza, more than 30,000 Palestinians, most of them civilians, have been killed. The Israeli ground invasion has displaced 2 million Palestinians within the Gaza Strip, many of them now forced into makeshift tents in and around the southern city of Rafah. In northern Gaza, vast swaths of which have been flattened by relentless Israeli airstrikes and artillery shelling, international experts warn that “famine is imminent”. Gazan children have already begun to die from lack of food.

As the war continues, how Israeli, Palestinian and American political actors understand Hamas is not merely a theoretical question; it is as much a material factor on the ground as bullets and tanks. It is one of the factors shaping military strategy, and will determine what kind of agreement can be reached to bring the current war to an end, and what the future of Gaza will look like.

The disintegration of Baskin and Hamad’s relationship thus reflects a larger and older debate about Hamas, one that has only become more urgent. At its core is a question about the essence of the organisation: whether it is primarily a nationalist group with an Islamist character, which could be a constructive player in a meaningful peace process, or whether it is a more radical, fundamentalist group, whose hostility to Israel is so unwavering that it can only play the role of violent opposition.

One camp in this debate, chiefly composed of western counterterrorism experts and US and Israeli security analysts, has long seen the group as defined by its violent hostility to Israel’s existence. According to this view, there was nothing surprising about 7 October. Instead, in the words of Matthew Levitt, a former Bush administration official and the author of a 2007 book on Hamas, it “demonstrated in the most visceral and brutal way that Hamas ultimately prioritised destroying Israel and creating an Islamist Palestinian state in its place”. Analysts of this school tend to point to Hamas’s vast tunnel infrastructure as evidence that the group protects its own fighters while leaving Gazan civilians above the surface to fend for themselves, without any system of bomb shelters.

An opposing, more heterogeneous camp, comprised of academics and thinktankers, many of them Palestinian, sees Hamas as a multifarious, complex political actor, divided between radical and moderating tendencies. Hamas, they argue, is the product of the reality under which Palestinians live – brutal occupation and blockade – and therefore potentially responsive to changes in those conditions. The problem, according to this view, is that even when Hamas leaders have appeared to be open to moderation, Israeli policy has made it impossible for the group to pursue this line without losing its credibility among Palestinians as the last-standing bastion of meaningful opposition to Israel and its occupation.

When we spoke in January, the Palestinian scholar Tareq Baconi said that “the major misconception” at the core of the dominant discourse about Hamas is the idea that “if Hamas as a security threat was undermined, Israel will have no issue with the Palestinians”. But if “Hamas were to disappear tomorrow,” he said, the Israeli blockade on Gaza and military rule in the West Bank would remain. “There’s this tendency to suggest that this is a war between Israel and Hamas rather than a war between Israel and Palestinians, which places Hamas outside of Palestinians,” he added. “It’s an inability to address the political drivers animating Palestinians.”

Khaled Elgindy, who is a former adviser to the Palestinian Authority (PA) leadership on negotiations with Israel and now a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute thinktank, argues that any postwar arrangement that excludes Hamas will be doomed to repeat the mistakes that led to the current war. “It’s exactly this notion of: ‘We’re going to make peace with this group of Palestinians while we make war with that group of Palestinians,’” which had served as the rationale for Israel’s economic suffocation and periodic bombardment of the Gaza Strip, he told me. “That’s nonsensical in terms of conflict resolution.”

“Hamas is a fact of political life in Gaza and in the Palestinian scene in general. And if anything, it is much more relevant today than it’s ever been,” Elgindy said. In an article for Foreign Affairs published late last year, he expanded on his view that Hamas must form part of a postwar settlement. The goal, wrote Elgindy, should be to incorporate Hamas and other hardline militant factions into the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the umbrella group dominated by the secular-nationalist party Fatah, which is recognised as the sole official representative of the Palestinian people on the world stage.

Elgindy believes that Palestinian politics could contain Hamas’s rejectionism alongside the Palestinian Authority’s cooperation with Israel, just as Israeli politics includes parties that support and those that oppose engagement with the Palestinian Authority. In the short term, he acknowledged, that might make “achieving a two-state solution harder, because they’re going to have a veto the same way any opposition does”. But in the long run, Elgindy continued, integrating Hamas into the PLO might begin to heal the persistent split in the Palestinian national movement, which has provided Israel with a convenient excuse for refusing to participate in any negotiations. If Hamas were to agree to abide by the agreements signed between Israel and the PLO, not only would this increase the chances that a peace agreement might last, it would also curtail Hamas’s ability “to act as a free agent and be the spoiler it can be”, Elgindy said.

At present, though, it seems highly unlikely Hamas leaders, in Gaza or abroad, would be willing to agree to a programme of the kind that Elgindy and others in what’s known as “the Middle East policy space” have sketched out. In early March, representatives from Hamas, Fatah and other Palestinian political factions reportedly met in Moscow for unity talks. Since the 2007 Hamas-Fatah war, there have been more than a dozen similar reconciliation attempts sponsored by a range of Arab and Muslim-led governments. None have translated into any durable arrangement.

But if Palestinian unity with Hamas may prove elusive, it is equally difficult to imagine a future without the militant group. “I think people believe this basic line, that if we destroy or at least marginalise Hamas, that will make peace more likely,” Elgindy said. In practice, he continued, this position rationalises Israel’s devastating continued assault on Gaza. This view is wrong, he said – not just strategically but morally.

Hamas was formed in 1987 by members of the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood against the backdrop of the first intifada, the popular Palestinian uprising ignited when an Israeli truck killed four Palestinian workers in Gaza’s Jabalia refugee camp. The group’s name, which means “zeal”, is an acronym for Harakat al-Muqawamah al-Islamiyyah, or the Islamic Resistance Movement. Historically, Palestinian Islamists had inclined toward political quietism, believing that Palestinian society had to be Islamicised if the fight against Israel were to be successful. Yet as demonstrations mounted, the struggle appeared to them as one they should lead.

Hamas’s founding leaders were, for the most part, refugees who had been born in what is now Israel and forced to flee to the Gaza Strip during what Palestinians call the Nakba, the displacement of roughly 700,000 Palestinians during the 1948 war. Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, the group’s spiritual leader, was born in 1936 in the village of Al-Jura, near the city of Ashkelon, in the south of present-day Israel. Diminutive and softly spoken, Yassin, who dressed in a white shroud and used a wheelchair owing to a childhood accident, seemed to his followers to embody the suffering of his people. In 2004, Israel assassinated Yassin, as it would many of Hamas’s leaders, when Israeli helicopters fired on his entourage as he left a mosque after prayers at dawn.

The organisation’s 1988 founding charter is a mixture of Qur’anic quotations, disquisitions on Islamic doctrine, nationalist declarations and conspiratorial antisemitism. The document defined the land of Palestine as a waqf, or Islamic trust, “consecrated for future Muslim generations until judgment day”, of which no inch could be given up. It accused Zionists of instigating the French and Bolshevik revolutions and labelled groups like “the Freemasons, the Rotary and Lions clubs” as “destructive intelligence-gathering organisations” that facilitated the “nazism of the Jews”. It subsumed the Palestinian national struggle under the banner of religious war. It was, in other words, an unlikely charter for a movement that, within a decade, would bid to represent the Palestinian cause, which had for the better part of the previous half-century been led by avowedly secular groups.

Whether the Islamic radicalism of the founding charter represents the operative ideology of the organisation has been debated almost since the group’s creation. Some scholars of Islamist politics see Hamas’s religious rhetoric as mainly a framework in service of its nationalist goals, which are its central concern. According to Azzam Tamimi, author of the book Hamas: A History from Within, the movement’s leaders realised that, as it grew, it needed a more accessible way of defining itself to the broader world. A document titled This Is What We Struggle For, written in the mid-90s in response to a request by a European diplomat for clarity on the group’s objectives, defined Hamas in rather different terms to those in the founding charter. Hamas was “a Palestinian national liberation movement that struggles for the liberation of the Palestinian occupied lands and for the recognition of Palestinian legitimate rights”. In a sense, the question of how to understand Hamas grows out of the gap between these two rhetorical modes: between uncompromising jihad and the language of anticolonial resistance, between fundamentalist ideology and political pragmatism.

“There is no single ‘Hamas,’” Tareq Baconi writes in his book, Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance. “It is an exercise in futility, as well as fundamentally inaccurate and reductionist to try to suggest that the movement is some form of monolithic actor,” Baconi continues. There are, within the organisation, hardliners and pragmatists, religious conservatives and comparative moderates, those who prioritise the armed struggle against Israel, and those, at least until recently, who sought gains through political means. Hamas has “always sought to play between the violent and the diplomatic tracks, to shift from one track to the other, whenever it saw its best interests as either”, says Hugh Lovatt, a Middle East expert and senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

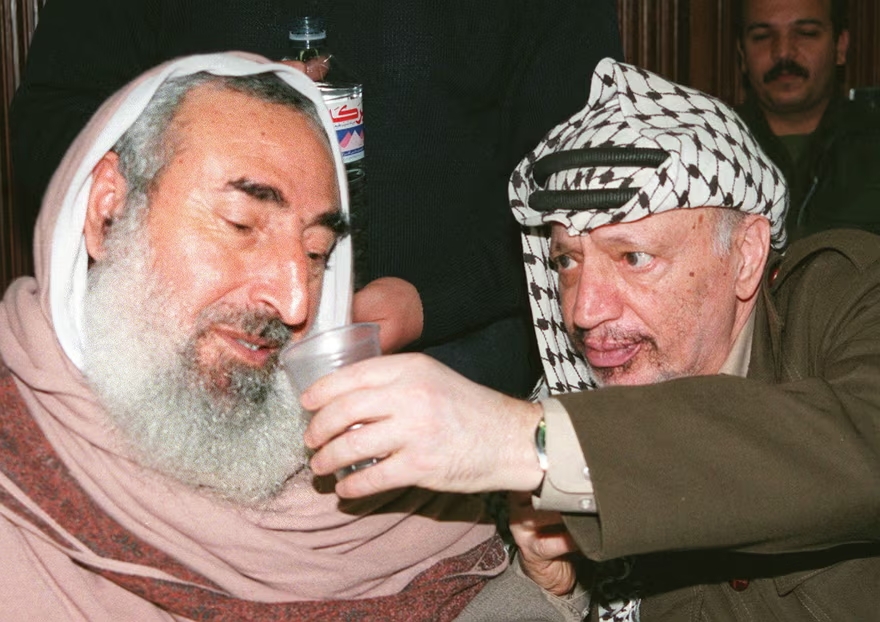

Yet if Hamas’s leadership was not always unified on matters of vision, the persistence of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza gave the group unity of purpose. In 1993, when the PLO, led by Yasser Arafat, recognised the state of Israel and renounced violence with the signing of the first Oslo accord, it was Hamas that claimed the mantle of armed resistance and commitment to liberating all of historic Palestine. The agreement between Israel and the PLO was a disappointment to many Palestinians, and not just supporters of Hamas. In a prescient 1993 essay, the Palestinian intellectual Edward Said called the Oslo Accords “an instrument of Palestinian surrender, a Palestinian Versailles”. Arafat had agreed to give up armed struggle against Israel and discounted the Palestinians’ “unilateral and internationally acknowledged claim to the West Bank and Gaza”, Said wrote, while “Israel has conceded nothing”.

Throughout the 1990s, Hamas, adamantly opposed to Oslo, intensified its fight against Israel. In its early years, its attacks had mainly taken the form of small arms fire, low-intensity roadside bombs and low-tech attempts to kidnap Israeli soldiers. That changed on 6 April 1994, when a Palestinian man, dispatched by one of the leaders of Hamas’s armed wing, blew himself up at a bus stop in the northern Israeli city of Afula, killing eight Israelis. It was expressly an act of vengeance in response to the massacre of 29 worshippers at the Ibrahimi mosque, carried out two months earlier by an Israeli extremist hoping to derail peace talks between the Israeli government and the PLO. The suicide bombing was also an expression of Hamas’s emerging military strategy. Hamas leaders saw civilian deaths as Israel’s weak spot, believing they would erode Israelis’ sense of personal security and, ultimately, reduce Israeli resolve.

The collapse of the Camp David talks in 2000, and the eruption of the second intifada, marked the transformation of Hamas into something more than just a spoiler. It emerged as a genuine challenger to the PLO and the institutions of the recently formed Palestinian Authority. The more Israel pursued settlement construction, and the more it entrenched the apparatus of military occupation, building checkpoints and walls, the more Fatah and the PA appeared to have capitulated, and the more Hamas’s uncompromising position gained in appeal. As the group mounted more suicide attacks through the 2000s, it also diversified its arsenal. In 2001, Hamas fired its first rockets from the Gaza Strip.

For Hamas’s leaders, this strategy of violence appeared to be vindicated in August 2005, as Israel began to withdraw its military and more than 8,000 settlers from the Gaza Strip. (By contrast, for Ariel Sharon, the Israeli prime minister at the time, the disengagement was a tactical move intended to sabotage future peace negotiations.) “Today you are leaving Gaza humiliated,” proclaimed Mohammed Deif, Ayyash’s successor and commander of the Qassam Brigades, in a videotaped message after the disengagement. “Hamas will not disarm and will continue the struggle against Israel until it is erased from the map.”

One perhaps surprising outcome of the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza was that while it seemed, to many in Hamas, to reflect the success of armed struggle, it was at this moment that the group appeared to shift its focus toward more conventional politics. Previously, Hamas had largely boycotted the electoral process, on the grounds that participation would have amounted to a recognition of the Oslo accords. Now, buoyed up by the Israeli withdrawal, Hamas contested the January 2006 legislative elections, running on an anti-corruption and law-and-order platform. To the shock of many in the PA, Israel and the Bush administration, Hamas won an outright majority. “I’ve asked why nobody saw it coming,” the US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice said at the time. The group that had long rejected the institutions created by the Oslo framework now had a popular mandate to lead them.

In contesting the elections, Hamas appeared to be deprioritising violence in favour of political engagement. “There are certain fundamental principles that they will not relinquish, but ultimately, they are not rigid in their approach,” said Tahani Mustafa, Palestine analyst at the International Crisis Group. “That doesn’t mean they’re going to give up the fight to liberate Palestine,” Mustafa added. “It’s just recognising what they want, and what reality will allow, and then trying to figure a middle ground between them.” Ahead of the legislative election, Hamas, led at the time by Khaled Meshaal, had signed on to the 2005 Cairo declaration, which affirmed the PLO as “the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people” and called for the establishment of the Palestinian state.

“Hamas had de facto acquiesced between 2005 and 2007 to a political programme that [might], if leveraged correctly, have led to the creation of a Palestinian state alongside Israel and the dismantling of the occupation,” Baconi wrote in an essay for Foreign Policy last November. But whether a Hamas-run Palestinian Authority would have used its popular mandate to pursue a Palestinian state alongside Israel, or if it would have harnessed the PA to pursue an intensified armed conflict, as Israeli leaders feared, we will never know. “Hamas’s gamble” – its shift to participation within the PA framework and endorsement of a Palestinian state on ’67 lines – “paid off,” Baconi writes in Hamas Contained, “in the sense that its bluff was never called.”

In response to Hamas’s 2006 electoral victory, Fatah members refused to join the Hamas-led government. Israel tightened its enclosure of the Gaza Strip. The US and European Union soon cut off aid. By the autumn of 2006, groups of Fatah and Hamas gunmen were carrying out assassinations, kidnappings and torturing each other’s loyalists, even as unity talks between Abbas and Meshaal continued. On 14 June 2007, after five days of fierce gun battles in Gaza, Hamas expelled the PA from the territory – and suddenly Hamas found itself in an entirely new role. It was now responsible for daily life in Gaza.

Sheikh Yassin once claimed that, during the first intifada, he had turned down an Israeli offer to take over the Gaza Strip. “It would have been crazy for us to consent to be mere stand-ins for Israeli rule,” he said. But now Hamas found itself with the task of administering a territory besieged by air, land and sea, and subject to near-routine aerial bombardment and artillery shelling by Israel.

Gradually, through the next decade and a half, Hamas consolidated its rule over the coastal enclave. To some, it seemed that Hamas had transitioned from a militant group with an ideology of armed opposition to a pseudo-state governing force. A quarter of its first elected cabinet boasted US graduate degrees. “They were never democratic or soft authoritarian, as some of the literature says,” Khalil Sayegh, a Gaza-born peace activist, told me. “They were hard authoritarian, but they were smart enough to deceive the west in how they dealt with the situation.” After expelling Fatah, Hamas moved on to limit the power of Gaza’s clans, which represented an alternative base of power. To clamp down on dissent and enforce conformity, Sayegh added, Hamas relied on tactics that ranged from public shaming to blackmail and torture.

Hamas never implemented sharia law, despite the push from some of the movement’s hardliners, but it did attempt, rather haphazardly, to legislate public morality. “Islamising measures are put forth tentatively, then retracted when citizens object,” a 2011 report by the Crisis Group found. At the same time, Hamas faced criticism from more radical Salafist groups for failing to impose strict Islamic law on the territory. In 2009, when al-Qaida-aligned Salafists declared an Islamic State in the southern Gaza Strip, Hamas forces violently crushed them during an assault on a Rafah mosque.

Hamas developed its elaborate system of tunnels to get around the harsh conditions of the blockade, as well as to shield its fighters from Israeli airstrikes. In particular, the tunnels connecting Gaza to Egypt became the besieged territory’s economic lifeline and a primary conduit for the smuggling of weapons. According to one estimate, in the mid-2010s, tunnel revenue provided the Hamas government with roughly $750m a year. Yet this was not nearly enough to prevent what the American political scientist Sara Roy has called the “de-development of Gaza”. While the first years of Hamas rule saw economic growth, between 2007 and 2022, real GDP per capita declined at a rate of 2.5% a year, as the population rose sharply. For much of the last decade and a half, UN officials have warned that Gaza was on the brink of a humanitarian crisis.

During these years, Hamas and Israel developed a mode of relating to each other – what Baconi calls an equilibrium of belligerency. Hamas rocket fire from Gaza became a means of negotiating with Israel. In return for pausing fire, Hamas would seek eased restrictions of the blockade or work permits for more Palestinian labourers crossing into Israel. In turn, Israel would retaliate to Hamas rockets with airstrikes and shelling – “mowing the grass”, as Israeli military strategists described it in their grisly euphemism – until it could claim it had sufficiently “deterred” Hamas from fighting until the inevitable next round.

For Israel, Hamas became useful as the functional government in Gaza, responsible for supporting the besieged Gazan population and containing the activities of other armed militant groups, much like the PA did in the West Bank. At the same time, Hamas maintained its claim to represent unbowed resistance to Israel. “There seemed to be some kind of modus vivendi between Israel and Hamas,” says Zaha Hassan, a human rights lawyer and senior legal adviser to the Palestinian negotiating team during Palestine’s bid for UN membership. (In the month leading up to 7 October, she added, “there was greater interaction and engagement between Israel and Hamas than there was between Israel and the PA.”)

To Netanyahu, this arrangement had an additional advantage. By keeping the PA-run West Bank and the Hamas-run Gaza Strip under separate administrations, Israel also kept the Palestinian national movement divided against itself, and therefore easier to manage. Over the course of a decade, Netanyahu’s governments helped prop up the Hamas administration in Gaza, facilitating the transfer of billions of dollars from Qatar to the Islamist group. “Netanyahu has always had a strong unspoken partnership with Hamas, which he has regarded as an invaluable asset in preventing the creation of a Palestinian state,” Hussein Ibish, a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute, told me via email. “His incredibly cynical divide-and-rule strategy, which he does not appear to have fully surrendered yet, led inexorably and virtually inevitably to 7 October.”

But Netanyahu was not merely cynical. He, like much of Israel’s defence establishment, appears to have genuinely believed that the burden of governance had led to a fundamental shift in the group’s strategic considerations – that Hamas, in effect, had been pacified.

It is now clearer than ever that Israel’s policy towards Hamas was built on a contradiction. On the one hand, Israel justified its punitive blockade and periodic bombardment of Gaza on the grounds that Hamas was a bloodthirsty terrorist group that sought Israel’s destruction. On the other, in Israel’s actual dealings with Hamas, it behaved as if Hamas had abandoned not just its commitment to destroying Israel but any alternative vision to occupation, and would be satisfied managing Gaza into perpetuity.

From within Hamas and among its supporters, however, the perception was very different. “2008-2009, 2012, 2014, 2021 – it’s continuous war,” Azzam Tamimi told me by phone from Istanbul, summing up this view. “Hamas has not been pacified. It’s just been fighting, and then there are breaks in the fighting.” This analysis is not so different from how much of Israel’s security establishment sees the group today. “Hamas has never stopped preparing for operations to respond to Israeli provocations,” Tamimi added. “I mean, the preparations for 7 October are not the sort of thing that happens overnight.”

Indeed, within Israeli defence circles, the cumulative failures of 7 October have been taken as proof that Netanyahu’s governments understood Hamas all wrong. A new common sense has begun to emerge. “We felt that if we bribed the organisation by providing it money or by enabling it to develop the economy, then it would become a more responsible and accountable sovereign,” said Kobi Michael, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies, a thinktank with close ties to Israel’s military, when we spoke in late December. “This is an illusion.” As Michael sees it, Israeli leaders failed to recognise that Hamas, at its core, is a “messianic” organisation that cannot be managed. “Theirs is a very religious way of thinking, which is irrational,” he said. “It was convenient for us to think that they are similar to us.”

As the war grinds on, Israeli policy analysts increasingly argue that the bellicose, maximalist rhetoric of Hamas’s leaders should be taken literally – that when they pledge to fight until Israel is destroyed, they mean it. “I read the other side’s writings in their original language, and I believe them, I simply believe them,” Michael Milshtein, an Israeli former intelligence officer, has said of Hamas’s Arabic publications and communiques. In his view, one major reason for the Israeli military’s colossal failure on 7 October was that the intelligence agencies and, even more fatefully, the country’s political leaders, forgot the nature of their enemy and failed to take notice of the manifold public threats issued by Hamas leaders that a massive armed operation against Israel was in the offing.

In the eyes of most Israelis, any semblance of peace will only be possible when Hamas no longer exists. Yet when Gershon Baskin and I spoke again in March, he told me that he and Ghazi Hamad had reconnected. The re-establishment of contact was mutual. “The first communication was about two months ago, which was an unpleasant back and forth,” he said. “The basic question is, could it be possible for us to have a constructive role [in making] a secret back channel,” Baskin added. “It’s not yet clear.”

Today, as 30 years ago, Hamas derives much of its popularity from Palestinian despair. “When oppression increases,” Sheikh Yassin told the late Guardian journalist Ian Black in 1998, “people start looking for God.” A survey conducted in December by the Palestinian pollster Khalil Shikaki found that 72% of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank believed that Hamas was correct in launching the 7 October attacks, despite the destruction Israel has unleashed. If, as many believe, Hamas will remain a force the day after the fighting stops – in what form, and with what consequences?

Proponents of incorporating Hamas back into the structures of Palestinian politics argue that the group’s leaders were once serious about pursuing the interim solution, of a Palestinian state on only part of historic Palestine, and that, under the right conditions, they might be willing to do so again. “It was real,” Hugh Lovatt said of Hamas’s openness to a two-state solution, which was expressed in the group’s 2017 revised charter. “There clearly is a political and relatively moderate wing within Hamas,” he continued. “The question is, what happens to them? Do they split from the movement? Will they be completely overwhelmed by the hardliners? Or do they find a way to steer the movement back toward the political track?”

Those who see a future role for Hamas in Palestinian politics as a necessity – a view that presupposes Hamas’s willingness to join the institutions it has hitherto scorned– argue that excluding Hamas would be undemocratic, as well as likely to guarantee future bloodshed. “Their inclusion is a prerequisite for creating a Palestinian leadership that is representative of its people,” Baconi told me when we spoke by phone, “regardless of what we think about their tactics or their ideology.”

At the same time, when I asked Baconi about the prospects of a return to the two-state paradigm after the war, he was not optimistic. “If there is a political process which would achieve a Palestinian state on ’67 borders – which I don’t think will ever exist, as in a state with real sovereignty – I do think Hamas, politically and strategically, would engage with it very effectively and would, I think, be pushed to recognise the potential of such a diplomatic process,” he replied. But against the backdrop of the total devastation of Gaza, talk of restarting the two-state process is mainly a distraction, Baconi added. “I don’t see any kind of effective political process coming out of this older discourse that takes us back to the 90s and early 00s.”

In all likelihood, the Hamas leadership’s willingness to re-engage in the political track may not be tested. “The idea of incorporating Hamas [into the PLO] is, I think, a brilliant one that is now politically impossible,” said Nathan Brown, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “You basically need the existing generation of American leaders to die off before it becomes politically feasible,” Brown said of the possibility of the US shepherding a process that saw Hamas enter the PLO. “And it’s unthinkable in Israel.”

Israeli public opinion has lurched even further right after the 7 October attacks. Benjamin Netanyahu’s popularity has tanked, but his replacement will not be a dove. And though it is true that, in the late 1980s and early 90s, the Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin agreed to talks with the PLO and Yasser Arafat, considered by most Israelis to be an unrepentant terrorist, the signing of the Oslo accords was only possible after the PLO had agreed to comply with a raft of preconditions. By contrast, no Hamas leader could ever totally renounce armed struggle or agree formally to recognise Israel.

There is a tendency to view events such as 7 October and the ongoing war through the prism of rupture. The death and destruction on such a massive scale appear to signal a shift in paradigm, the emergence of a new phase. But part of what makes Israel’s prosecution of the current war so chilling is that, after killing more than 30,000 Palestinians, and after 1,200 Israelis were killed by Hamas on 7 October, the basic political framework of Israel/Palestine may, the day after the war, remain the same as it was on 6 October.

Discussion about this post