By THE NEW YORK TIMES

Under pressure from Beijing, officials in Hong Kong are scrambling to pass a long-shelved national security law that could impose life imprisonment for political crimes like treason, a move expected to further muzzle dissent in the Asian financial center.

The law known as Article 23 has long been a source of public discontent in Hong Kong, a former British colony that had been promised certain freedoms when it was returned to Chinese rule in 1997. Now, it is expected to be enacted with unusual speed in the coming weeks.

China’s Communist Party officials, who have pressed the city to push through this law, appeared in recent days to make their urgency clear. After meeting with a senior Chinese official in charge of Hong Kong, the city’s top leader, John Lee, reportedly cut short his visit to Beijing to return to the city, vowing to get the law “enacted as soon as possible.” The Hong Kong legislature and Mr. Lee’s cabinet, the Executive Council, hastily called meetings to discuss the law.

The full draft of the law was only made public for the first time on Friday, as lawmakers began to review it. It targets five offenses: treason, insurrection, sabotage, external interference, and theft of state secrets and espionage.

Mr. Lee said the law is necessary to close gaps in an existing national security law imposed by Beijing in 2020 that was used to quash pro-democracy protests and jail opposition lawmakers and activists. Mr. Lee has depicted Hong Kong as a city under mounting national security threats, including from American and British spy agencies.

China has sought to tighten its grip over Hong Kong after massive antigovernment protests in 2019 engulfed the city, posing the greatest challenge to Beijing’s rule in years. Many protesters had taken to the streets to push back against Beijing’s encroachment over the city and its erosion of Hong Kong’s civil liberties, but Chinese officials said the demonstrations were instigated by Western forces seeking to destabilize the territory and China.

Critics say the new security law will stifle more freedoms in the city of 7.5 million people by curbing their right to speech and protest, while also further diminishing the autonomy Hong Kong is granted under a “one country, two systems” formula with China.

Legal experts say criticism of the government can now be interpreted as sedition, a crime that carries a prison sentence of up to seven years, which can be increased to 10 years if it involves collusion with an “external force.”

“This law will have far-reaching impacts on human rights and the rule of law in Hong Kong,” said Thomas Kellogg, the executive director of the Georgetown Center for Asian Law. “It’s clear that the government is continuing to expand its national security tool kit to crack down on its political opponents.”

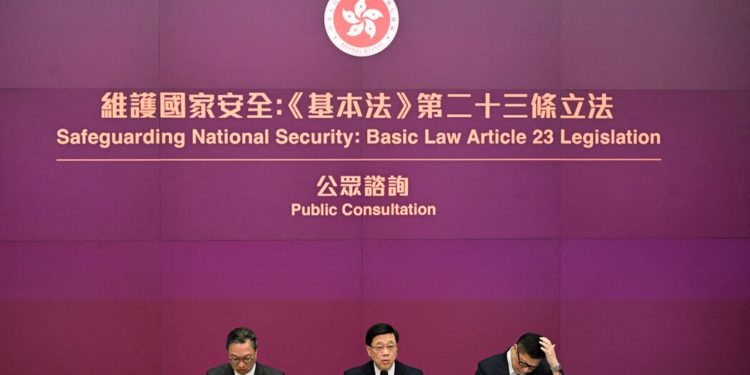

The government has sought to show that the legislation is widely accepted, pointing to a one-month period of public consultation — based on a document that described only in broad terms the scope of the law — that officials said drew mostly supportive comments.

But the Hong Kong Journalists Association has expressed concerns about the law over the potential new limitations on press freedom. And the Bar Association of Hong Kong had recommended that the law’s definition of sedition include the intention to incite violence, to narrow the scope of the offense. But the draft of the law did not include such language.

The bill unveiled on Friday also proposed extending the time a person suspected of endangering national security can be detained, without charge, to as many as 14 days, from a previous limit of two days. The law would also empower the police to seek permission to block a suspect from consulting a lawyer if access to legal advice were deemed detrimental to national security.

Mr. Kellogg said the speed in which the government was moving to enact the law suggested that concerns raised in the consultation period were not likely to have been taken seriously.

“This does indeed suggest that the government did not really plan to seriously engage with public submissions, and that they were likely going to execute on their planned legislation from the get go,” Mr. Kellogg said.

Andrew Leung, the president of the Legislative Council, defended the move to speed up the passage of Article 23. “I also fully agree that there is a genuine and urgent need for the legislation,” he said at a news conference on Friday.

Hong Kong officials have invoked national security legislation in Western countries such as the United States, Britain and Canada to justify the need for Article 23. Legal experts, however, argue against such a comparison, noting that Hong Kong, unlike democratic societies, does not maintain a system of checks and balances to counter abuse.

In a speech at the legislative session on Friday, Chris Tang, the Hong Kong security secretary, said the proposed legislation had safeguards and struck a balance between national security and human rights.

“Innocent people will not be caught by the law inadvertently,” Mr. Tang said.

Foreign business officials say the legislation will make it harder to explain to investors the differences between Hong Kong and mainland China. Foreign diplomats also worry Article 23 could discourage local organizations from having regular interactions with consular staff because of the law’s broad emphasis on external interference.

The bill is expected to pass in the coming weeks without opposition in a legislature overwhelmingly stacked with pro-establishment lawmakers. In 2021, Beijing imposed a drastic overhaul of the electoral system that effectively disqualified opposition candidates by allowing only candidates considered “patriots” to run.

The government first tried to enact Article 23 in 2003, but retreated after hundreds of thousands of residents who were concerned that it would limit civil liberties held major protests.

Olivia Wang contributed research.

Discussion about this post