By AL JAZEERA

War is on the doorstep of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Goma city and the region is at breaking point, activists and aid workers have said, as the United Nations sounds an alarm over the situation in the Central African country.

“One Congolese person out of four faces hunger and malnutrition,” Bintou Keita, the head of the UN’s DRC peacekeeping mission MONUSCO, told the UN Security Council this week, warning of a rapidly deteriorating security situation and a humanitarian crisis reaching near catastrophic levels.

“More than 7.1 million people have been displaced in the country. That is 800,000 people more since my last briefing three months ago,” she said.

Heavy fighting between the Congolese army and armed group M23 has intensified in the eastern part of the country since February, forcing hundreds of thousands of civilians to flee their homes as the rebels make territorial gains.

The armed group “is making significant advances and expanding its territory to unprecedented levels”, Keita said at the UN on Wednesday.

This comes as fierce battles between the army and rebels have reached the outskirts of Sake, a village about 25km (15.5 miles) from regional economic hub Goma – marking a major advancement for M23.

‘War is at the door’

About 250,000 people fled their homes between mid-February and mid-March, according to UN figures, with the vast majority seeking shelter in and around Goma. Pockets of makeshift tents have popped up along roads or desolated areas with no access to basic aid.

“Things are at a breaking point,” said Shelley Thakral, a World Food Programme spokesperson, after returning to Kinshasa from a trip to Goma. “It’s quite overwhelming – people are living in desperate conditions,” she told Al Jazeera. Many people have fled in a hurry with no belongings and now find themselves in cramped camps with little prospect of returning, she added.

The effects are also being felt inside Goma, where civilians have seen the price of basic commodities skyrocketing and health services being disrupted by a steady stream of refugees coming in. “The situation is at its worst and war is at the door,” said John Anibal, an activist with civil society group LUCHA based in Goma.

As the fighting spreads, it is also intensifying. According to ACLED, an independent data-collecting group, the use of explosives, shelling and air raids since the start of this year has quadrupled compared with the average in 2023.

Rwanda links

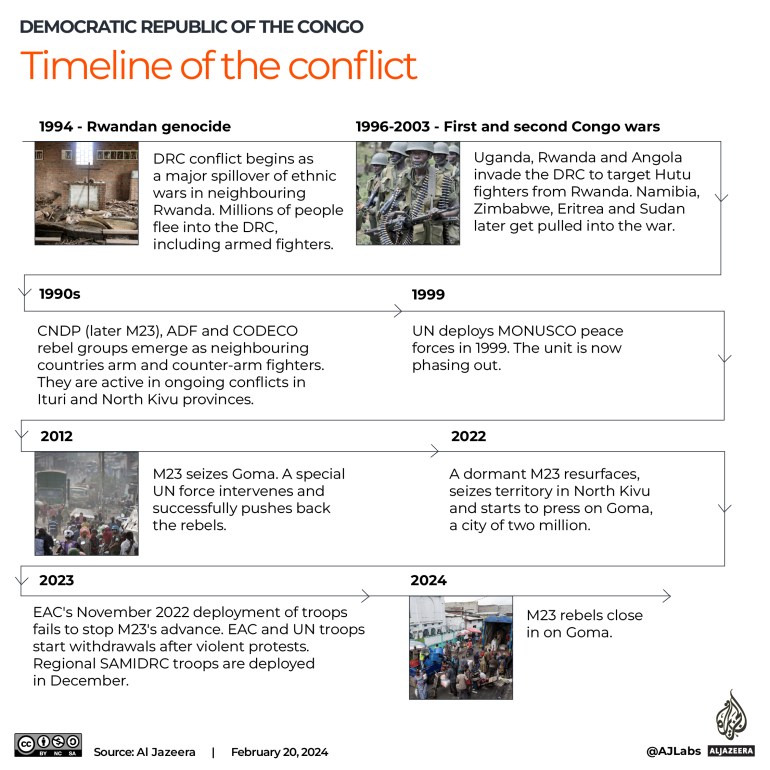

The eastern region of the DRC has been plagued by violence for 30 years.

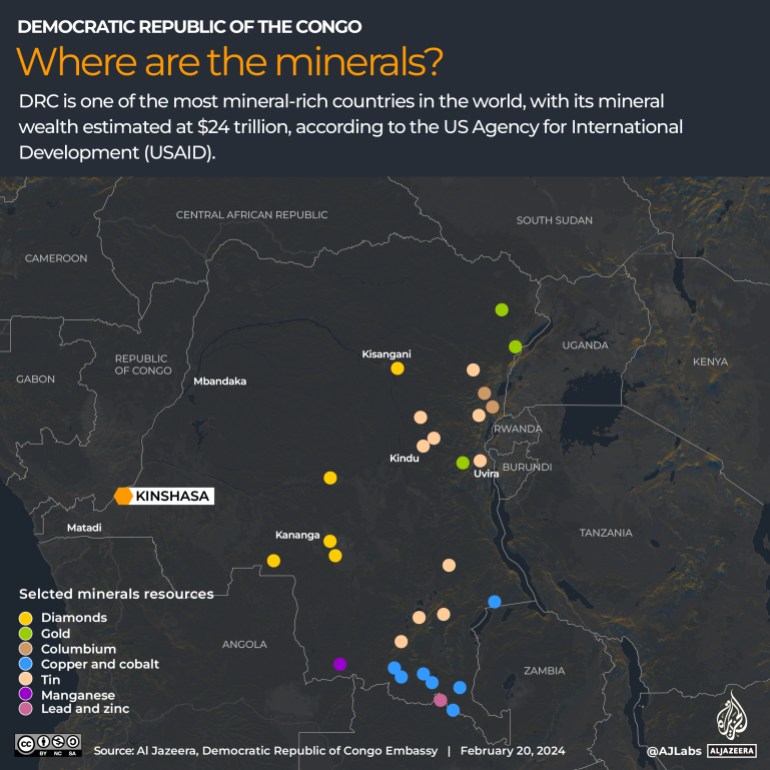

More than 200 armed groups roam the area, vying for control of its minerals, including cobalt and coltan – two key elements needed to produce batteries for electric vehicles and gadgets, such as PlayStations and smartphones.

Among the groups, M23 has posed the biggest threat to the government since 2022 when it picked up arms again after being dormant for more than a decade. Back then, it had conquered large swaths of territory, including Goma, before being pushed back by government forces.

The conflict in eastern DRC is also deeply intertwined with the Rwandan genocide. In 1994, more than 800,000 Tutsis and Hutus were killed by violent Hutu armed groups. In the wake of the fighting, Hutu genocidaires and former regime leaders fled to the DRC.

Today, Kigali accuses Kinshasa of supporting one of the Hutu armed groups present in eastern DRC, the FDLR, which it sees as a threat to its government. And the DRC, alongside the UN and the US, have accused Rwanda of backing the M23. Kigali has denied this.

At the UN Security Council meeting on Wednesday, the DRC’s ambassador to the UN Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja called on the intergovernmental body to take a stronger stance against Rwanda.

“The council must cross the Rubicon of impunity and impose on Rwanda sanctions commensurate with its crimes,” said Nzongola-Ntalaja.

Rwanda responded heatedly. The country’s UN representative, Ernest Rwamucyo, said that “ethnic cleansing targeting Congolese Tutsi communities reached unprecedented levels”.

‘Addressing partial symptoms’

The renewed fighting has come at a delicate moment for the country as the MONUSCO mission is pulling out of the country after 25 years at the request of the Congolese government. The first phase of the withdrawal is expected to be complete by the end of April, and all peacekeepers will leave by the end of the year.

The government of President Felix Tshisekedi accused the UN mission of failing to protect civilians. Instead, it gave soldiers of an East African regional bloc the mandate to fight back against the rebels.

But that ended last December after the president accused the regional force of colluding with the rebels instead of fighting them. So he turned to another force, SADECO, composed of southern African nations to do the job.

Observers are sceptical that this new mission will succeed where its predecessors failed.

“I don’t see this as a stabilising intervention, at most, it will postpone the issue because there is no one military solution,” said Felix Ndahinda, a researcher on conflict in the Great Lakes Region.

Structural weaknesses in governance, lack of state presence in remote regions and interethnic rivalries, are among causes that the state is failing to address, Ndahinda told Al Jazeera.

“In the last 30 years, different interventions have been addressing partial symptoms of the problem rather than looking at the full picture – till that is not done, you can only postpone, but not resolve, the issue,” Ndahinda said.

Discussion about this post