By THE NEW YORK TIMES

China’s premier will no longer hold a news conference after the country’s annual legislative meeting, Beijing announced on Monday, ending a three-decades-long practice that had been an exceedingly rare opportunity for journalists to interact with top Chinese leaders.

The decision, announced a day before the opening of this year’s legislative conclave, was to many observers a sign of the country’s increasing information opacity, even as the government has declared its commitment to transparency and fostering a friendly business environment.

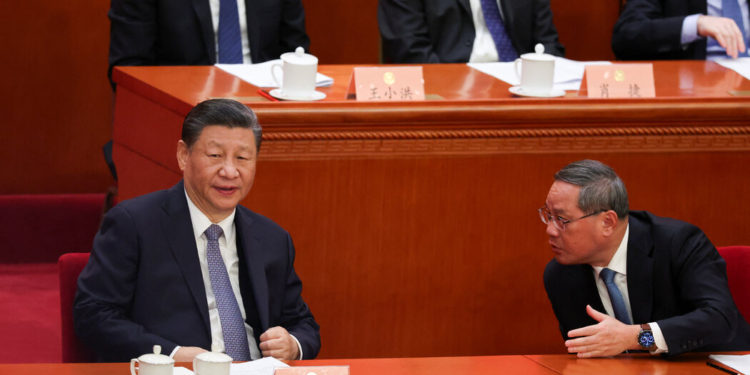

It also reinforced how China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, has consolidated power, relegating all other officials, including the premier — the country’s No. 2, who oversees government ministries — to much less visible roles. China’s current premier, Li Qiang, was widely considered to have been elevated to the role last year because of his loyalty to Mr. Xi.

“Barring any special circumstances, there will not be a premier’s news conference in the next few years after this year’s legislative session either,” Lou Qinjian, a spokesman for the legislature, said at a news briefing about this year’s session.

Mr. Lou offered few details about the decision, except to say that there would be a greater number of question-and-answer sessions with lower-level officials instead.

On Chinese social media, censors were closely regulating discussion of the change. The comments sections of many official news reports about the announcement were closed. On the popular platform Weibo, a search for the hashtag “There will be no premier’s news conference after the closing ceremony of this year’s legislative session” — the language used in the official reports — returned an error message: “Sorry, this content cannot be displayed.”

China’s premier has hosted a news conference at the end of the annual legislative meeting, known as the National People’s Congress, since 1993. Though the answers rarely departed from the official line, it was a rare chance for journalists — including foreign ones — to ask questions directly of top leaders.

At past conferences, reporters have asked premiers about issues ranging from the price of vegetables in Beijing to alleged human rights abuses and the possibility of direct elections. In 2012, the news conference by China’s then-premier, Wen Jiabao, lasted three hours; journalists asked about self-immolations by Tibetans protesting Chinese rule and a political scandal engulfing Bo Xilai, the Communist Party secretary of a major city.

The next day, Mr. Bo was dismissed from his position and was later charged with and convicted of bribery.

Chinese officials had held up the exchanges as proof of the country’s increasing openness.

“There are always sensitive and difficult questions from journalists, and the premier always resolves them with confidence, wisdom and humor,” said a 2018 article posted on social media by an official account of the legislature. The premier’s news conference, it continued, “has become an important window for observing China’s openness and transparency. Through it, countries around the world can feel the pulse of contemporary China’s reform and opening up, and its democratic political development.”

But since Mr. Xi came to power in 2012, he has tightened controls over the press and speech. Even routine data about the economy — the heart of the premier’s portfolio — has become more and more limited, especially as China’s growth has flagged in recent years.

The premier’s news conference, too, has become increasingly scripted. Reporters’ questions have long been vetted in advance, but the space for asking about sensitive issues has decreased.

And the role of the premier itself has been greatly diminished. The first premier to serve under Mr. Xi, Li Keqiang, was seen as relatively liberal and had championed giving markets a greater role in the economy. In 2020, Mr. Li made headlines when he used unusually stark language to describe the plight of poor Chinese, at a time when China was promoting its success in eliminating poverty. At his annual news conference that year, he said there were still 600 million people whose income was “not even enough to rent a room in a medium-size Chinese city.”

But over Mr. Li’s decade as premier, his influence continuously waned, as Mr. Xi promoted aides seen as more loyal to himself and emphasized security and ideology over economic growth. The current premier, Li Qiang, a former aide to Mr. Xi, replaced Li Keqiang in March last year. Li Keqiang died of a heart attack in October.

During Li Qiang’s news conference after the congress last year, his first — and as it would turn out, likely his last — in the role, he expressed support for the private sector, amid concerns about China’s economic recovery from three years of coronavirus restrictions. But he nodded often to Mr. Xi and offered few specifics.

And in the year since, Mr. Li has largely kept a lower profile than his predecessors. He has attended fewer international meetings, and has flown on chartered flights, according to state media reports — not the special jets reserved for top officials generally used by previous premiers.

Neil Thomas, a fellow for Chinese politics at the Asia Society Policy Institute, said the cancellation of the news conference would erode the premier’s visibility even further. It “helps entrench the notion that there is no alternative to Xi’s leadership,” Mr. Thomas said.

Keith Bradsher contributed reporting, and Li You and Siyi Zhao contributed research.

Discussion about this post