By AL JAZEERA

Film critics last year were practically clambering over one another to heap praise on Oppenheimer, Hollywood’s blockbuster treatment of the man known as the father of the atomic bomb, Robert Oppenheimer.

The New York Times hailed the biopic as a “drama about genius, hubris and error, both individual and collective, [that] brilliantly charts the turbulent life of the American theoretical physicist who helped research and develop the two atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II — cataclysms that helped usher in our human-dominated age”.

Widely expected to take home the Academy Award for Best Picture, Oppenheimer depicts its eponymous protagonist as a heroic – albeit complicated – figure, who created the hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) only to later denounce the proliferation of nuclear warheads, although curiously enough, he never expressed any public remorse for his invention’s Japanese casualties.

And while the film goes to elaborate lengths to interrogate Oppenheimer’s inner turmoil, scenes of the hellish conflagration on the ground at Hiroshima and Nagasaki are nowhere to be found in the three-hour epic.

Oppenheimer’s solipsism is representative of a Hollywood film industry that is at once an outlier and trendsetter in world cinema, said Tukufu Zuberi, the chair of the sociology department and professor of Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Oppenheimer gives you the idea that something noble was happening in the creation of the atomic bomb,” Zuberi told Al Jazeera. “But it wasn’t; the bomb wasn’t needed to end the war. The Japanese had already surrendered. We bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki to show the world – principally the Soviet Union – what happens when you go up against the United States.”

The demonstration of shock and awe at Hiroshima and Nagasaki “was central to NATO’s mission and the military-industrial complex that the United States depends on to do business with the rest of the world”, Zuberi said. “Now, welcome to 2024; there are so many wars going on that it is unbelievable, and they all hinge on this certain narrative about the past and you have to tell these narratives that make people feel OK about that.

“The last thing you want is a film that says that the military-industrial complex introduced a new process for settler colonialism and that is based on white supremacy.”

‘The most important of the arts’

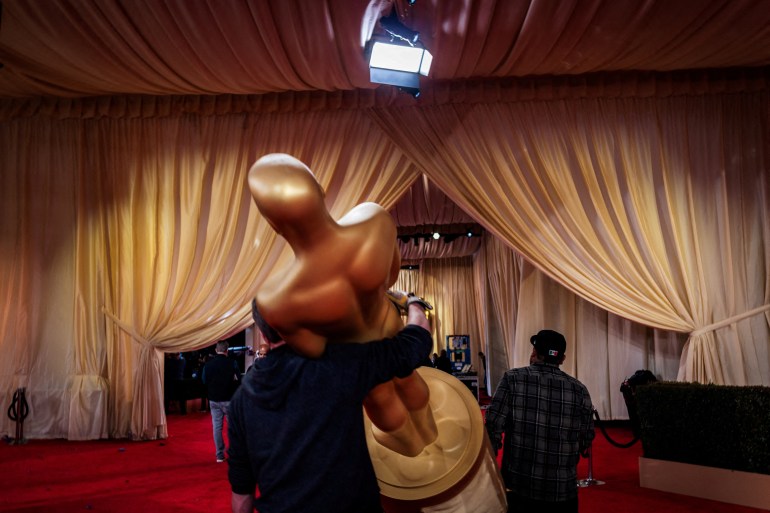

Sunday night’s Academy Awards is the marquis night for Hollywood’s film industry. But while cinema might be the biggest cultural US export, its international reputation is tarnished by its tendency to romanticise – if not altogether ignore – the West’s dispossession of much of the world, especially the Global South, several film scholars told Al Jazeera. This is because the primary purpose of Hollywood movies is to entertain, and not to raise consciousness, prompt social transformation or challenge class relations, such as the Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 classic, The Battle of Algiers, Senegalese director Ousmane Sembene’s Black Girl, released the same year, or Asghar Fahradi’s 2011 masterpiece, A Separation, to name just a few.

“By and large, Hollywood is not wired to produce revolutionary movies,” said Nana Achampong, director of the department of creative arts at the African University in Accra, Ghana. “They are wired to produce movies that placate, that comfort, that make people feel good.”

Film historians generally attribute the world’s divergent cinematic oeuvres to the defining political tension of the 20th century, that of capitalism versus communism. Proclaiming that “cinema for us is the most important of the arts”, Vladimir Lenin nationalised the Soviet Union’s film industry in an effort to shape a national identity and unite Russian tribes that the tsars historically pitted against each other. Consequently, the Russian auteur Sergei Eisenstein’s films – most notably the Battleship Potemkin and Strike – stand in stark contrast to racist Hollywood films such as Gone With the Wind, or Birth of a Nation, directed by Eistenstein’s rival, DW Griffith.

From its early years, cinema developed along two different tracks, with much of the world parroting Italy’s post-war gritty neorealism, while Hollywood followed its own path with romantic scripts intended to anaesthetise the population’s revolutionary impulses by glamorising the individual rather than the community, and exhorting obedience to authority.

Keeping alive the lie of white settler colonialism

The 2023 blockbuster, Killers of the Flower Moon, is a case in point, Zuberi said. Directed by Martin Scorsese, and nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, the movie depicts the criminal prosecution of a corrupt local political boss, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, for stealing oil-rich land from Native Americans in Oklahoma in the 1920s.

“This is presented as some kind of exceptional activity but it was in fact US policy to steal land from Indigenous people,” Zuberi said. “Hardly anyone went to jail.”

From Brazil to India’s Bollywood, Mexico to Turkey and Argentina to Nigeria, the film industry has taken off as more and more countries attempt to make sense of the colonial era, and its aftermath. In comparison to these more recent offerings, it is not uncommon to hear Africans describe the typical Hollywood fare in terms that might be used to describe cartoons: amusing but banal, or a lark that elicits a chuckle but is ultimately unsatisfying. Zuberi, however, said it is not entirely accurate to describe Hollywood films as Orientalist – the term coined by Palestinian scholar Edward Said to describe Western efforts to justify colonialism through artistic misrepresentations – because most studio executives in the US are painfully unaware of the historical consensus.

Adisa Alkebulan, professor of Africana Studies at San Diego State University and a film scholar, told Al Jazeera: “They [Hollywood executives] are only looking for these interesting stories that they think an audience might respond to and not so much a story that might necessarily raise the consciousness of a particular group of people.”

Since 29 African and Asian nations met in 1955 in Bandung, Indonesia, Africa’s film industry has largely sought to narrate the continent’s independence struggle in intimate and innovative ways. Zuberi cites as one example, the 1973 Senegalese film, Touki Bouki, which is, to put too fine a point in it, Ferris Buehler’s Day Off in an anticolonial context.

Both Zuberi and Achampong, however, have identified a shift in world cinema towards the blockbuster style innovated by Hollywood, in an attempt to reap a financial windfall. Increasingly, African films feature the romantic comedy formula popularised by Hollywood, or the exceptional Black protagonist murdering his foes one by one, with each killing more bloody than the last.

“The primary role it [Hollywood] serves is to make money,” Todd Steven Burroughs, an author and adjunct professor of Africana studies at Seton Hall University told Al Jazeera. “But while making money it imports values and brutal manipulation of sound, text, audio, etc, knowing the impact it’s having on the nervous system. But it’s more complicated than just saying all art is propaganda, and I don’t disagree with that. As an individual who consumes media, I consume these things and I enjoy them, but I have to always think about what is the psychological impact of it. America and most people around the world are anti-intellectual. Most people have not studied what the role of mass communications is.”

Said Zuberi: “You can look at what’s going on in Gaza right now and clearly see that Hollywood’s cinematic narratives are loaded with justifications of the Israeli state.

“Really, a big part of Hollywood is just keeping alive the lie of white settler colonialism.”

Discussion about this post