By THE NEW YORK TIMES

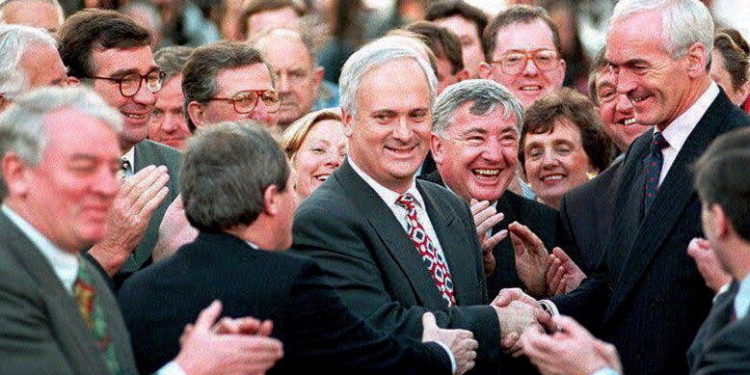

John Bruton, a former Irish prime minister who led an alliance known as the Rainbow Coalition and played a central role with Britain in an effort to secure peace in Northern Ireland after decades of strife, died on Tuesday in Dublin. He was 76.

His family said his death, in a hospital, followed a long illness; they did not specify the cause. Mr. Bruton had also served as the European Union’s ambassador in Washington.

Feted in death across the political spectrum in Britain and Ireland, Mr. Bruton had a long career in the center-right Fine Gael party. He was his country’s prime minister, or Taoiseach (pronounced TEE-shack) in Irish, from 1994 to 1997, a time when Britain was led by Prime Minister John Major of the Conservative Party.

The governments in Dublin and London had long acknowledged that they each played a major role in navigating the treacherous sectarian and political divisions of warring Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland.

Mr. Bruton saw his diplomatic mission as, in part, to counter the suspicions of Northern Ireland’s Protestants, who largely sought and still seek continued union with Britain as part of the United Kingdom. Many Protestants feared that the peace effort would dilute their ability to steer events and forestall a united Ireland.

Such was Mr. Bruton’s readiness to calm Protestant nervousness that rival politicians in the predominantly Catholic Ireland took to calling him “John Unionist.”

But he also took issue with Mr. Major’s mistrust of the mainly Catholic Irish Republican Army, which sought a unified Ireland and declared a cease-fire in 1994 as part of the effort toward peace. Specifically, Mr. Bruton challenged Mr. Major’s skepticism about the I.R.A.’s assurances that its forces were prepared to decommission their weapons.

Still, Mr. Bruton was also mistrustful of the I.R.A. and condemned its use of violence in pursuit of political aims. But he agreed to talk to Gerry Adams, the head of the group’s political wing, Sinn Fein, even though the two were widely reported to be deeply suspicious of each other’s motives. Mr. Bruton severed this so-called back-door line of communication in 1996, after the I.R.A. had reneged on its cease-fire by bombing the Docklands area of East London.

In public, Mr. Bruton and Mr. Major cultivated an image of statesmanlike collaboration. In 1995, for instance, they drew up a framework agreement committing participants in the peace effort to “peaceful political means without recourse to violence or coercion.” The framework, moreover, foresaw “parity of esteem and treatment” between Northern Ireland’s fractious communities.

It foreshadowed the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which, among other things, established an elected, power-sharing executive authority to be run by these onetime adversaries, ending 30 years of bloodletting that had claimed more than 3,000 lives.

In private, however, the two prime ministers sometimes clashed to the point that in 1996, Mr. Major threatened to hang up on Mr. Bruton, who was known for displaying a short temper. The two men were on the phone speaking about an incendiary march through a Catholic area in Northern Ireland by hard-line Protestants.

According to an official Irish government account, Mr. Bruton told Mr. Major that his government’s handling of the march suggested that it was not in charge of the situation. Mr. Major snapped back, “If you want to continue the conversation in that fashion, you can continue it alone.” After the ruffled feathers, they resumed their dialogue, averting any major setback.

While Mr. Major and Mr. Bruton worked to advance peace negotiations, both were undone by the domestic politics of their own countries. In 1997, elections brought the Labour Party leader Tony Blair to power in Britain and Bertie Ahern, of the center-right Fianna Fail party, to the prime ministership in Ireland, enabling them to preside over the Good Friday Agreement.

In response to the news of Mr. Bruton’s death, Mr. Major said, “In testing circumstances, he put peace above political self-interest to progress the path toward the end of violence.”

John Gerard Bruton was born on May 18, 1947, to Joseph and Doris (Delany) Bruton, members of a prosperous farming family near Dublin. His brother, Richard Bruton, also played a prominent role in Irish politics.

John studied politics and economics at University College Dublin and qualified to become a barrister at King’s Inns, Ireland’s oldest law school, though he did not practice law. He became the youngest member of the Irish legislature at age 22, representing Fine Gael in the Meath voting area near Dublin.

In 1978, he married Finola Gill, a fellow political campaigner, and they had four children — Matthew, Juliana, Emily and Mary-Elizabeth. His wife and children survive him along with a sister, Mary, and his brother.

Mr. Bruton served twice as finance minister of Ireland with mixed results. In 1982, he sought to raise government income by imposing a value-added tax on children’s shoes. The move was so unpopular that it collapsed the government through defections of coalition members and enabled political adversaries to depict him as an out-of-touch man of wealth.

But he was also credited with promoting a cut in corporate taxes that drew foreign investment and helped create the so-called Celtic Tiger economic boom.

Mr. Bruton took over leadership of the Fine Gael party in the early 1990s. He was 47 when he became prime minister in 1994 as head of the Rainbow Coalition — an alliance of Fine Gael, the Labour Party and a smaller left-wing party, the Democratic Left.

Assuming office, he hung a portrait of John Redmond, a moderate turn-of-the-century Irish politician, on his office wall to signal that he planned to take a conciliatory approach toward governing and toward Britain.

Mr. Bruton was known as an ardent Europhile and an opponent of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union. Such E.U. credentials led him to become the bloc’s ambassador to Washington from 2004 to 2009. His primary mission was to ease strains with the administration of George W. Bush over the invasion of Iraq and trade issues.

Despite a whiff of corruption among his lieutenants, Mr. Bruton coupled peace efforts with domestic achievements. Among them, he sponsored a referendum that narrowly overturned his country’s constitutional ban on divorce. In 1995, he welcomed then-Prince Charles to Ireland, the first official visit by a British royal family member since the country gained independence in 1921. While British newspapers castigated him for seeming over-effusive about the visit, Mr. Bruton insisted that it had enhanced the often-fraught relationship between London and Dublin.

In 1997, his Rainbow Coalition seemed set for re-election, but its Labour Party ally lost ground, and the alliance was defeated. Mr. Bruton was replaced as prime minister by his rival, Mr. Ahern. Still, when Mr. Bruton died, Mr. Ahern said he “wouldn’t have a bad word to say” about him.

Discussion about this post