By WIRED

Kindle libraries; troves of infinitely streamable songs on Spotify and Apple Music; scores of shows and films on Netflix, Max, and Hulu. Even the Criterion Collection is online now. Cultural archives now live on server farms, so much so that the value of physical media seems ever-shifting. While there’s some benefit to it—the ineffable experience of flipping through a book, owning DVDs of your favorite show to watch when it disappears from streaming—the logistical issues involved in preserving massive archives of these things feels astronomical. Especially now, when many shows, comics, and albums aren’t even released as Blu-rays, bound editions, or LPs.

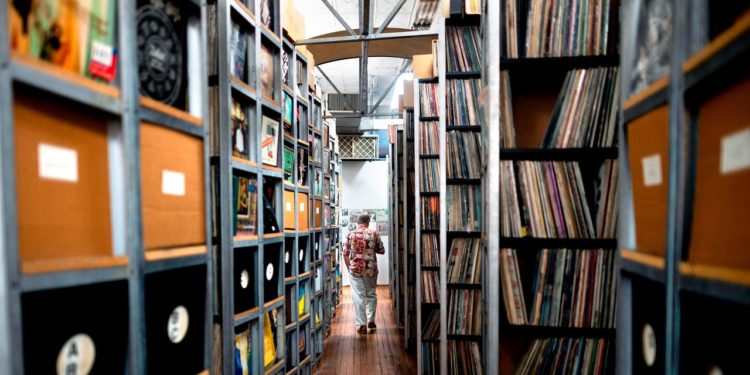

While physical media faces an increasingly uncertain and unsympathetic future, its defenders do all they can to protect what they see as an invaluable resource. Nowhere is that more evident than at the ARChive of Contemporary Music (ARC), a New York-based nonprofit that keeps and maintains the largest popular music collection in the world.

Encompassing more than 3 million recordings, including the personal holdings of collectors like Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards, businessman Zero Freitas, late director Jonathan Demme, and A-Square Record label founder Jeep Holland, the ARC holds an impressive array of everything from signed LPs to blues 78s to Brazilian and Haitian music. It’s also taken in recordings, books, and papers from music icons like David Byrne and journalist Jon Pareles, and reportedly holds some of the world’s biggest collections of Broadway, African, punk, jazz, country and western, folk, hip hop, and experimental recordings. It’s become an important resource for researchers doing work in music history, graphic design, or cultural heritage—and it’s in jeopardy.

Created in New York City in the mid-’80s, the ARC was originally envisioned by founders B. George and the late David Wheeler, an author and record collector, as a way to help preserve the legacy of an industry that, at that time, frankly hadn’t done a very good job of keeping track of its own history. Sessions deteriorated and went missing over time, private pressings of LPs went into personal collections and never reappeared, and entire label catalogs were lost to moldy basements and unsentimental relatives.

As the ARC grew, it pushed out of the boundaries of its previous spaces, landing three years ago in a private commercial space in upstate New York held by hotelier André Balazs. Now, the ARC says it has to leave that space because, unbeknownst to them and to Balazs, the building they’re occupying—known as “The Piggery”—is zoned for agriculture, a designation that can’t be changed. They’ve already received a million-dollar donation from a longtime supporter who’d love to see them move into a new space, but no one else has come out of the woodwork to chip in.

B. George, an artist and record label founder who used his own 47,000-disc collection to seed the ARC, says the organization is looking for a benefactor like James Smithson, who donated the equivalent of $500,000 in gold sovereigns to the United States to found the Smithsonian, despite never visiting America. ARC, he says, needs someone “who can see the value in what we’re doing and who has the foresight to push America to do something that they should have always been doing all along.”

Discussion about this post