By AL JAZEERA

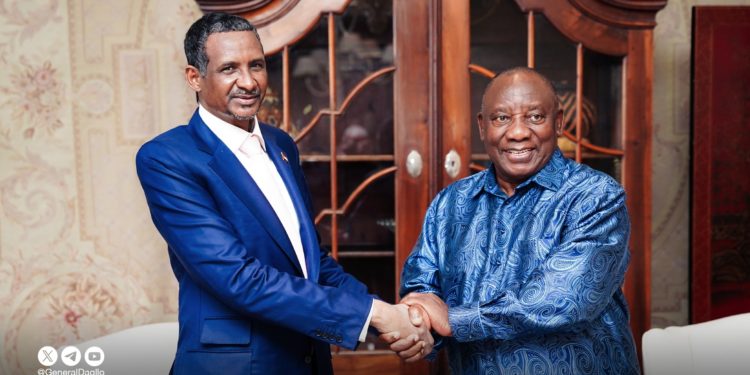

When General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the leader of Sudan’s paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and former deputy chairman of the Transitional Sovereignty Council of Sudan, landed in Gauteng, South Africa on January 4 for talks with President Cyril Ramaphosa, he looked civil and dapper in a navy blue suit.

His calm, confident and businesslike demeanour implied he was on a mission to rescue Sudan from the violent excesses of his obstinate adversaries in the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

Thus, as Dagalo, known widely as “Hemedti”, posed for pictures with a smiling Ramaphosa, he did not look like a rogue military commander who is alleged to have overseen horrendous war crimes – torture, extrajudicial killings and mass rape among others – in Darfur in 2014 and 2015.

Standing proudly next to the president of Africa’s second wealthiest nation, acting like a dignified and magnanimous statesman, he did not look like a vicious, power-hungry military operative who had just nine months ago launched a devastating civil conflict that already killed 12,000 people and displaced over seven million others.

Hemedti’s recent rebranding as a mainstream political leader and a rightful representative of the Sudanese people – achieved through well-advertised performances of camaraderie not only by Ramaphosa but also the leaders of Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda among others – is of course nothing but a charade.

Since the beginning of Sudan’s latest civil war, Amnesty International says, fighters from both Hemedti’s RSF and al-Burhan’s SAF have committed egregious human rights violations and war crimes including deliberate attacks on civilians, attacks on civilian infrastructure like churches and hospitals, mass rape and other sexual violence.

The RSF has also been accused of driving the Masalit people out of Sudan’s volatile West Darfur region through an ethnically targeted campaign of violence, sparking fears of a new genocide in the region.

At best, Hemedti, who has acquired a dubious fortune by seizing gold mines and selling gold, is a political reincarnation of his former boss, ousted Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, who ruled with an iron fist, rigged general elections, stifled dissent through systemic violence, and only paid lip service to constitutional freedoms for 30 years.

At worst, he is a rebel without a cause, palpable ideology, or moral compass who appears determined to exploit the Sudanese people’s genuine struggle for democratic change for his own political ends.

After he met with Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni on December 27, Hemedti said unnamed figures from al-Bashir’s old regime and the “misguided leadership of the Sudanese Armed Forces” seek to impede the peace process and prolong the war. And he claimed he was engaged in a military effort to “rebuild the Sudanese state based on new, just foundations”.

Then, on January 2-3, Hemedti held talks with the leader of the Coordination of Civilian Democratic Forces (Taqaddum), Sudan’s former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. These discussions concluded with the two leaders signing the Addis Ababa Declaration, supposedly a comprehensive blueprint for peace talks and civilian rule. However, Malik Agar, the deputy chairman of Sudan’s ruling Sovereign Council, dismissed the plan as “an agreement between partners, as Taqaddum and the RSF are essentially one body with two faces”, adding “there is nothing new or groundbreaking here”.

That Hemedti appears to have developed a newfound appetite for civilian rule at a time when the RSF has been scoring significant military victories against its rivals, including the capture of Wad Madani, the country’s second city, comes as no surprise.

All along, Hemedti’s goal has been to defeat his adversaries militarily and use these victories to proclaim himself as the legitimate leader of his country.

Like many other former rebels who have needlessly pushed their people into armed conflict while pretending to be working for peace, because continuous fighting helped them obtain or maintain political power, Hemedti shows newfound but questionable commitment to advance an unimpeded constitutional order and avoid a return to war sometime in the future.

As a rebel leader whose primary motivation for fighting appears to be accumulating personal power rather than improving the living conditions of his people, Hemedti is more similar to Jonas Savimbi, the founder of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), than any other political figure in Africa.

Following a power struggle that broke out soon after Angola gained independence from Portugal in November 1975, Savimbi waged a 27-year intermittent civil war against the ruling People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA).

The cold-war conflict, in which Russia supported the MPLA and the US, alongside apartheid South Africa, backed UNITA, killed one million people and made four million others homeless.

For 27 years, Savimbi foiled several peace initiatives from the United Nations and the Organisation for African Unity – the predecessor to the African Union (AU). Despite the leading role he played in the continuation of the devastating conflict, however, he was accepted as a legitimate political player who should have a say over the country’s future. He was treated as a mainstream political figure, and even an anti-colonial hero, by many African leaders and was also hosted by then US President Ronald Reagan at the White House in 1986.

In November 1994, amid growing pressure from both the UN and AU, UNITA finally signed the Lusaka Protocol, which called for a permanent ceasefire, demobilisation of UNITA’s troops, and the integration of UNITA’s military and political wings into government departments.

The protocol, however, was never fully implemented, largely due to Savimbi’s desire to continue the conflict that was the primary source of his power and political relevance. With MPLA similarly not interested in ending the conflict, for four long years the two parties continued to purchase arms and provoke each other while supposedly negotiating for a permanent end to hostilities. Ultimately, in 1998, UNITA’s refusal to demobilise its soldiers and submit UNITA-controlled areas to a civilian authority led to the complete breakdown of the Lusaka Protocol.

After the demise of Lusaka, UNITA and the MPLA continued to fight, and cause immense suffering to the Angolan people, until the latter killed Savimbi in February 2002. Only two months after the rebel leader’s killing, the two parties managed to reach a permanent ceasefire agreement and end the war for good.

Suffering from a conflict similarly fuelled by leaders more interested in consolidating power than building peace, Sudan must learn from Angola’s 27-year-long civil war, and the failures of the Lusaka Protocol.

Although several African leaders, who could not care less about everyday Sudanese, seem to have embraced Hemedti’s sudden and highly suspect metamorphosis from vicious commander to democratic statesman, just as it was the case with Savimbi, there is little reason to believe he is genuine in his newfound commitment to building peace and establishing civilian rule. RSF forces have, after all, already failed to adhere to international humanitarian law and protect civilians after agreeing to do just that in the Jeddah Declaration of May 2023.

Thus, the mistakes made in Angola more than 20 years ago should not be repeated in Sudan today. A peace agreement must facilitate the complete disbandment of the RSF, ensure Sudan’s army makes a long-awaited return to the barracks, and lay the groundwork for a feasible transition to free, transparent and credible multiparty elections. To back up a new dispensation, the United Nations Security Council must impose an arms embargo on all parties to the conflict and undertake a key role in implementing peace. Most importantly, Hemedti – or any other commander who played a role in Sudan’s ongoing devastation – should not be allowed to reinvent himself as a democrat and sacrifice any prospects for sustainable peace in pursuit of power.

In Angola, Russian and US financial, military and diplomatic support for warring parties fuelled a catastrophic civil conflict for years, diminishing fragile prospects for peace in the country.

To prevent a repeat of this avoidable catastrophe, foreign actors backing the RSF and the SAF, such as the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, must end their meddling in Sudan’s internal affairs at once and stop supporting the personal agendas of power-hungry commanders like Hemedti and al-Burhan.

The welfare and aspirations of everyday Sudanese must take precedence over the narrow interests of Sudan’s military complex and the self-serving agendas of regional and global powers.

A democratic Sudan will have no place for people like al-Burhan and Hemedti.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

Discussion about this post