By THE NEW YORK TIMES

Vowing to “break taboos,” deregulate the economy and fight to the last against the extreme right, President Emmanuel Macron presented his vision of a stronger, more just France during a televised news conference that lasted deep into the Parisian night on Tuesday.

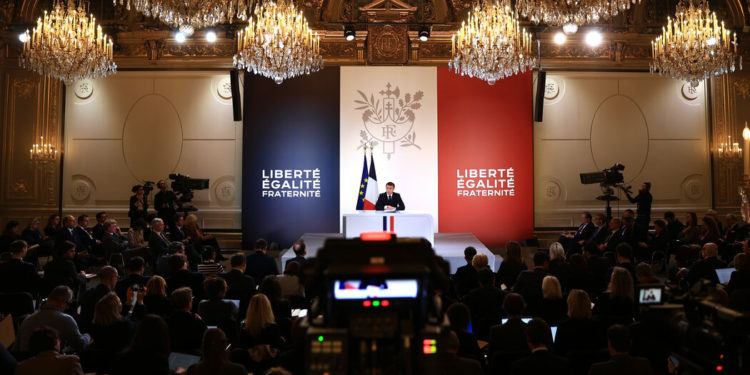

“We will put an end to useless norms,” Mr. Macron said in an appearance before more than 100 journalists, promising to favor those who “innovate and create,” cut red tape, facilitate hiring and encourage the unemployed to take up job offers. His goal, he added, was “a France of good sense rather than a France of hassles.”

The president noted that he had defeated Marine Le Pen, the far-right leader and perennial presidential candidate, in 2022 and 2017, and “I will do everything to stop her again.” He described her National Rally party’s program as incoherent and a guarantee of a weaker France.

“Until the last 15 minutes of my presidency, I will fight,” he said.

In a France already troubled by pro-market changes pushed through in Mr. Macron’s first term, which brought unemployment to its lowest level in many years, his promise of renewed deregulation was certain to meet resistance from the many French people attached to a high degree of state-financed social protection.

“We have had too many taboos,” Mr. Macron said. One of the strongest in France surrounds any suggestion that too many entitlements may lead to diminished competitiveness.

Mr. Macron’s decision to address the nation, in the week after he named a new government led by the youngest prime minister in the history of the Fifth Republic, was a response to the sense of drift that has characterized his second presidential term.

Audacity! Action! Daring! These were the words Mr. Macron adopted as the drumbeat of a performance that lasted more than two hours, as if willing a divided and dubious France to unite and advance with Gabriel Attal, 34, its newly appointed prime minister.

During the 20 months since he has taken office for the second time, Mr. Macron, who is term-limited and must leave in 2027, has presided over tumultuous overhauls of the legal retirement age and immigration policy, while Ms. Le Pen steadily advanced in the polls. His shake-up at the start of a new year is designed, at least in part, to ensure that Ms. Le Pen is not his successor.

“Hers is the party of lies,” he said. “Hers is the party of easy anger.” In a world marked by rapid technology-driven change, instability and war, he asked whether a France “all alone in a weakened Europe would be a good thing.”

Seated on a podium, looking down on journalists, Mr. Macron offered an extended, at times professorial, disquisition on the state of France and its place in a troubled world. He described the United States as a “democracy in crisis,” which, he said, reinforced the need for Europe to unite and become capable of protecting itself.

A Russia that had flouted international law through its invasion of a neighbor “cannot be allowed to win in Ukraine,” he said.

If one of Mr. Macron’s themes was a push for greater dynamism, another was the quest for a more just country.

Mr. Macron said the government would work harder to reduce inequality, especially in schools, where, he said, homework assistance would be reinforced, access to culture improved and students better assisted in charting their futures.

He also announced an experiment in using uniforms in 100 schools this year, which, if successful, would lead to their adoption throughout the French school system in 2026. He described school uniforms as levelers that had the merit of hiding social differences.

“We have improved some things but not radically changed them,” Mr. Macron said. “The worst of injustices is inequality at the starting line.” He added, “I want to put an end to the France of ‘this is not for me,” which he described as a betrayal of the promise of the Republic.

Improving education will clearly be a central concern of Mr. Attal’s new government. But still only half-formed, it is off to a shaky start.

Having said that education was his “absolute priority,” Mr. Attal has watched his new education minister, Amélie Oudéa-Castéra, make a series of blunders so crass that there have been calls for her resignation.

When it emerged, shortly after her appointment, that she and her husband, a pharmaceuticals executive and the former chief executive of one of France’s top banks, send their three children to an elite private school, she explained her rejection of the French public education system by saying that her oldest son had lost countless hours because no teacher had turned up in his classroom.

Staff of the public school in central Paris that her older son had attended before his parents moved him to a conservative private Catholic school contested this claim. Such was the outcry that Ms. Oudéa-Castéra was obliged to apologize for impugning the performance of teachers. She was booed on Tuesday upon her arrival at the public school.

Asked if the minister should resign, Mr. Macron said she had been “clumsy” but had offered an apology, “which was the right thing to do.” Her choice of a private school for her three sons “must be respected,” he added, suggesting that with time and the cooperation of teachers, Ms. Oudéa-Castéra would succeed.

Aurelien Breeden contributed reporting from Paris.

Discussion about this post