By THE OBSERVER UG

Ugandan students who have completed master’s programs in Algeria are forced to do bachelor’s programs back in Uganda before their qualifications get recognized by Ugandan professional bodies.

Algeria stands out as one of the top destinations for Ugandan students on scholarship. The country has been sponsoring students since the 1990s, and the annual scholarship allocation has now reached an average of 100.

These students embarked on diverse academic journeys, pursuing STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) bachelor’s and master’s degrees across fields like medicine, allied health, engineering, architecture, and beyond. On average, those voicing their frustrations have dedicated between 4 to 7 years to their studies in the Maghreb country, with some in the medical field spending up to a decade pursuing their education.

This year, the ministry Education was granted 200 slots, and 39 have been awarded so far. However, data from the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE) reveals a challenging scenario. Between 2018 and the present date, the council has only managed to equate qualifications for only 74 students. This statistic alone points to a significant obstacle in the processing and recognition of qualifications obtained by students studying in Algeria.

Confronted with the complexities of having their papers equated, a substantial number of scholarship recipients opt not to return to Uganda. Instead, they explore opportunities in countries like Canada, France, and Belgium, where they perceive smoother transitions and potentially more favorable prospects.

For instance, in 2009, Richard Basoma Bagaiga’s dream took flight with an Algerian scholarship for electronic engineering at Abou Bekr Khalid University. Little did he know that upon returning home after seven years, his triumph would morph into a frustrating saga. NCHE has since then failed to acknowledge his qualifications, leaving him unable to secure a professional license, contract, find employment, or advance his studies.

“It’s hectic, and it seems like I didn’t study,” laments the once-proud electronic engineer, who, by Algerian standards, holds a master’s level education. He shared the hardships he has faced since returning home, shedding light on a challenging chapter in his life.

“It’s really hectic, it is almost like I didn’t study because unless you get a job and someone knows you. But for a good job, they cannot give you contracts. They cannot, for example, to the extent that even if I do research they cannot value the research. I’m stranded there,” he says.

Despite years of efforts to have his academic papers equated, NCHE only took up his case in October 2022. Although the process typically concludes within three months, a year later, he has yet to see any results. Bagaiga has consistently visited the NCHE every month, where he is assured that his qualification concerns are actively being addressed. However, there are instances where he is overlooked, intensifying his frustration.

Bagaiga’s predicament is not an isolated case; the frustration echoes among numerous Algerian-educated students. Like him, many have been recipients of scholarships to pursue studies in foreign lands. However, they find themselves ensnared in a protracted battle for qualification equivalence and acknowledgment by professional bodies that has spanned several years.

Nicholas Ndiba serves as another poignant example, having pursued a bachelor’s degree in microbiology in Algeria, only to confront formidable challenges upon his return. NCHE and the Allied Health Professionals Council (AHPC) became significant hurdles in his endeavors.

Ndiba says initially, AHPC offered him the option to undergo an examination to get a license. However, this option was later revoked, exacerbating his frustration with the intricate processes of qualification equivalence and recognition by professional bodies. Faced with these challenges, a disheartened Ndiba decided to return to university in Uganda. Currently, he actively pursuing a bachelor’s degree in biomedical laboratory sciences within the Ugandan educational system.

“I have suffered. I went to Allied Health Council and I was told microbiology cannot be given a license. I’m a scientist but in my country, I cannot work because I don’t have a license. I was advised to do another course in Uganda that can get me a license. Right now, I’m doing a bachelor’s degree in biomedical laboratory – years I actually studied for 4 years in Algeria. Allied Health Council told me to do an exam then they stopped it and told me to do a course again,” he said.

Eng Emmanuel Opio Elasu, another student educated in Algeria, underscores that a significant number of graduates attribute blame to the NCHE, alleging the utilization of an incorrect method in the qualification equivalence process. Consequently, many students encounter challenges when attempting to register with their respective councils.

“The problem here is most of the engagements are on the number of years and not the credit units and the contents…You realize that at Makerere University, a credit unit even the guys of architect, it is I think 120 but if you critically check on those guys’ things, they do more than 120,” he said.

Elasu further accentuates the predicament that numerous courses pursued by students in Algeria, particularly in natural and life sciences, are currently unavailable at the undergraduate level in Uganda. In contrast, these courses in Algeria encompass crucial specialties like microbiology, parasitology, and immunology, among others.

“The thing that has caused problems so much, some courses do not exist here in Uganda but they are specialties that are so big in Algeria like microbiology, astrology, immunology, you get? Now those ones we do not have them here at bachelors level. So once they have done them and they do masters and they come back to Uganda, they literally do not know where to place them,” said Elasu.

He goes on to highlight that while students in the field of medicine may sometimes have the opportunity to transition to the Ugandan system, there is a lack of a clear structure from the Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council (UMDPC) regarding the procedures for joining the body.

He explains that some students are required to undergo internships, some are mandated to take examinations, and others engage in both. Notably, for those choosing the examination route, there is a conspicuous absence of clear guidelines provided by the UMDPC regarding the timing of these examinations.

“NCHE needs to contemplate a standardized system of entry into the council, open to everyone for the benefit of the medical fraternity. Allied Health Professionals Council should consider evaluating internship opportunities for graduates or subjecting them to examinations to qualify, instead of rejecting the courses,” Elasu recommended.

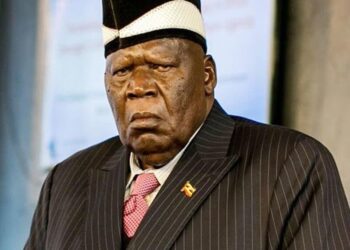

During the engagements last week, some students expressed their frustration when given the chance to meet with officials from NCHE and some officials from the minister of Education in charge of higher education John Chrysostom Muyingo.

Many students, interviewed on the sidelines of this event, observed a systemic issue with how government institutions handle matters. They noted that professional bodies, NCHE, and the ministry of Education are working in isolation, leading to a failure to address even the most fundamental issues raised by the students.

Dr Vincent Ssembatya, director for quality assurance at NCHE, acknowledged that the NCHE is facing challenges in equating the qualifications of students from various countries, including Algeria. He pointed out that the issue lies in the differences between the education systems of Algeria and Uganda, making the process of equivalence somewhat challenging.

For an extended duration, Algeria adopted the French-related classique system of higher education. However, in recent times, they transitioned to the LMD (license-masters-doctorate) system. Under the classique system, it was customary for students to progress directly from A’levels to a five-year master’s program, a practice uncommon in Uganda.

Significantly, numerous medical, engineering, and architectural programs in Algeria still adhere to the classique system. Architectural students face an additional challenge as their program spans three years, contrasting with the standard four-year duration for similar programs in Uganda. This difference in program duration contributes to the intricacies involved in comparing and recognizing qualifications between the two countries.

Ssembatya highlights that students from Algeria often submit qualification papers indicating programs lasting over seven years. The council faces challenges in understanding how to equate such extended programs to recognized ones in Uganda.

“It is not easy, but we don’t want to return your qualification and say it is not equivalent to anything we know. Some degrees are seven years, seven years. So now what is this? A PhD? It is seemingly beyond bachelor’s but we don’t want to say it is bachelor’s just because we are lazy. Is it masters? But it is not equivalent to something we have here,” added Ssembatya.

He further said that some students enroll in non-recognized institutions, resulting in non-equatable qualifications. Meanwhile, others attend recognized institutions but end up with qualifications that are also non-equatable.

“We also encounter cases of countries where their councils for higher education are non-responsive. We send inquiries via email, and this process can seemingly last forever. Algeria is one of the countries facing this issue, and we’ve observed a similar problem with Cameroon,” he added.

Mary Lisa Nalusiba, who completed her studies this year, expressed that she returned alone from her cohort.

“Many are hesitant to return to Uganda, understanding that the process of equating their qualifications or obtaining practice licenses from various professional bodies in Uganda could be very challenging,” she said.

Bagaiga explains that while the option to work in other countries exists, he faces unique challenges. He cannot easily relocate due to his familial commitments, with a wife already holding a stable job in Uganda.

The hurdles faced by these students have prompted concerns from minister Muyingo. He underscored that the country secured these scholarships with the primary goal of facilitating knowledge and skills transfer, particularly in STEM courses. Expressing worry that these challenges might result in trained students hesitating to return to Uganda, he emphasized the urgent need for resolution.

Muyingo offered guidance, suggesting that the ministry of Education conducts thorough cross-checks on the curriculum before sending students on various courses. Additionally, he advocated for the establishment of collaboration with professional bodies and other pertinent stakeholders to ensure that the courses pursued abroad align equitably with those offered in Uganda.

Hajj Muzamil Mukwatampola, commissioner in charge of admissions and students affairs at the ministry of Education highlighted that the ministry is actively pursuing solutions to address this issue before enrolling each student for studies in Algeria.

Ssembatya highlighted that with ongoing efforts to establish a Common Qualifications Framework at the African Union level, there is potential for significant improvement in addressing the challenges faced by students in equating qualifications.

“The implementation of a standardized framework could enhance the recognition of academic achievements across member states, fostering easier comparison and understanding. This, in turn, may facilitate greater mobility for students and professionals, encouraging seamless transitions between countries,” said Ssembatya.

He further noted that the cooperation between the Common Qualifications Framework and professional bodies could guarantee the alignment of academic qualifications with established professional standards, mitigating concerns regarding licensing upon returning to their respective home countries.

Discussion about this post