By AL JAZEERA

Eight years after the image of three-year-old Alan Kurdi lying facedown on a beach in Turkey shocked the world, pictures of asylum seekers’ lifeless bodies washed up on the coast of Italy’s Calabria region in February once again stirred global outrage.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen responded to the tragic shipwreck just metres away from the coast of Steccato di Cutro by promising to “redouble our efforts”.

“Member states must step forward and find a solution. Now,” she said.

Yet as 2024 begins, activists and experts told Al Jazeera that 2023 has seen Europe reach for ever more drastic solutions to curb NGO search and rescue operations and outsource its border management to other nations.

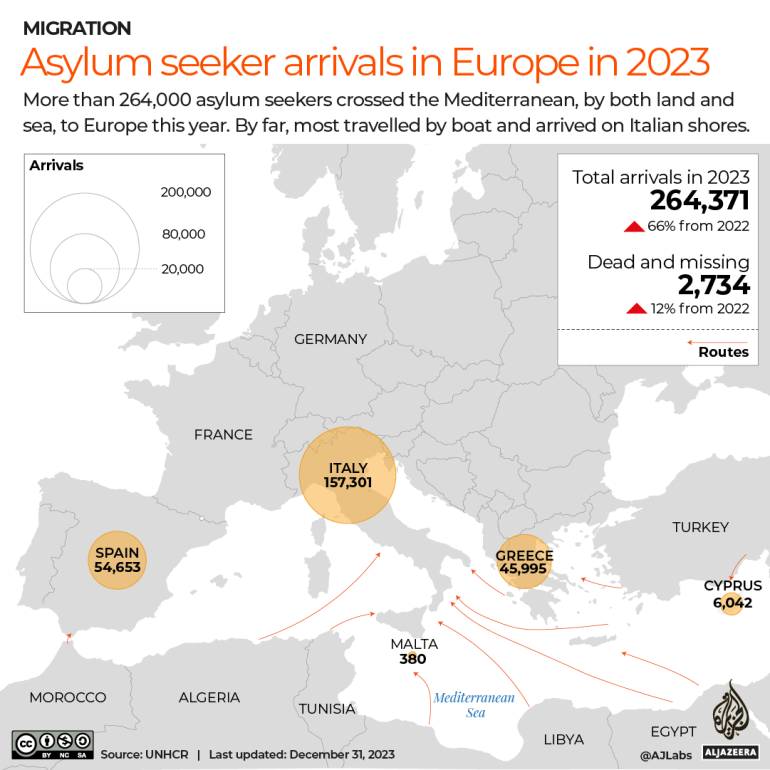

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimated at least 2,571 people died this year trying to cross the Mediterranean – one of the deadliest years ever. Since 2014, the United Nations agency has counted at least 28,320 men, women and children who lost their lives trying to reach Europe.

“What is new is the popularity of the idea that you can externalise asylum processing,” said Camille Le Coz, associate director for Europe at the Migration Policy Institute. “That’s something we’re likely going to see more of moving forward despite shaky legal grounds.”

Externalising asylum

At least 264,371 asylum seekers entered Europe by boat and land in 2023, according to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees – a 66 percent increase compared with the previous year and the highest figure since 2016. Six of every 10 among them landed on Italian shores.

Flavio Di Giacomo, a spokesperson for the IOM, said these numbers were a far cry from those recorded in 2015 when more than a million people reached European shores via the sea.

“There is no real emergency,” Di Giacomo told Al Jazeera. “They are very manageable figures, and more should be done to give people who arrive by sea access to a system of protection.”

Yet hardliners have sounded the alarm about migration. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was accused in December of adopting “toxic” rhetoric after warning that migration would “overwhelm” European countries without firm action.

His comments came during a four-day political event in Rome organised by far-right Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, weeks after his flagship bill designed to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda to process their claims was ruled unlawful by the Supreme Court in the United Kingdom.

Meloni, who also governs on a staunchly nationalist agenda that focuses on immigration, has warned that Italy would not become “Europe’s refugee camp”.

Similarly to her British ally, Meloni had signed a deal to send asylum seekers arriving in Italy to another country. Albania had agreed to process their claims in two facilities run by Italian officials under Italian jurisdiction. The five-year deal, announced in November, was blocked by the Balkan country’s Constitutional Court for violating the constitution and international conventions.

Le Coz told Al Jazeera that Georgia, Ghana and Moldova were also in talks with European Union member states to sign deals to conduct part or all of their asylum procedures on their territory. Whether these agreements will be greenlit by courts next year is unclear.

“Deals that externalise asylum processing raise questions in terms of human rights standards but also on political and financial costs,” Le Coz said. “In the end, none of these deals are moving forward because their legal grounds are pretty shaky, and so far, they have provided no solutions while incurring many costs.”

Amid renewed interest in external processing, the EU has been working on a New Pact on Migration and Asylum to make return and border procedures on European soil “quicker and more effective”.

The pact, which reached a preliminary agreement on December 20 after lengthy negotiations ahead of further debate in the coming months, allows member states to fast-track the processing of applications from countries with low approval rates, such as Morocco, Pakistan and India, and foresees tougher rules in case of emergencies, including longer detention periods.

NGOs have denounced the pact as a “devastating blow to the right to seek asylum in the EU”, arguing that the measures erode international protection standards.

“It will normalise the arbitrary use of immigration detention … and return individuals to so called ‘safe third countries’ where they are at risk of violence, torture, and arbitrary imprisonment,” a group of 50 civil society organisations said in an open letter.

“Human rights cannot be compromised. When they are weakened, there are consequences for all of us,” the letter added.

According to Le Coz, the impact the pact is going to have on the ground next year remains unclear. “On one hand, there is concern that the system is going too far in terms of quick processing of the asylum claims, and on the other hand, there are political forces betting on the fact that the pact is not going to deliver and that we should move towards further deals with foreign governments like Albania and Rwanda,” the analyst said.

Border patrol

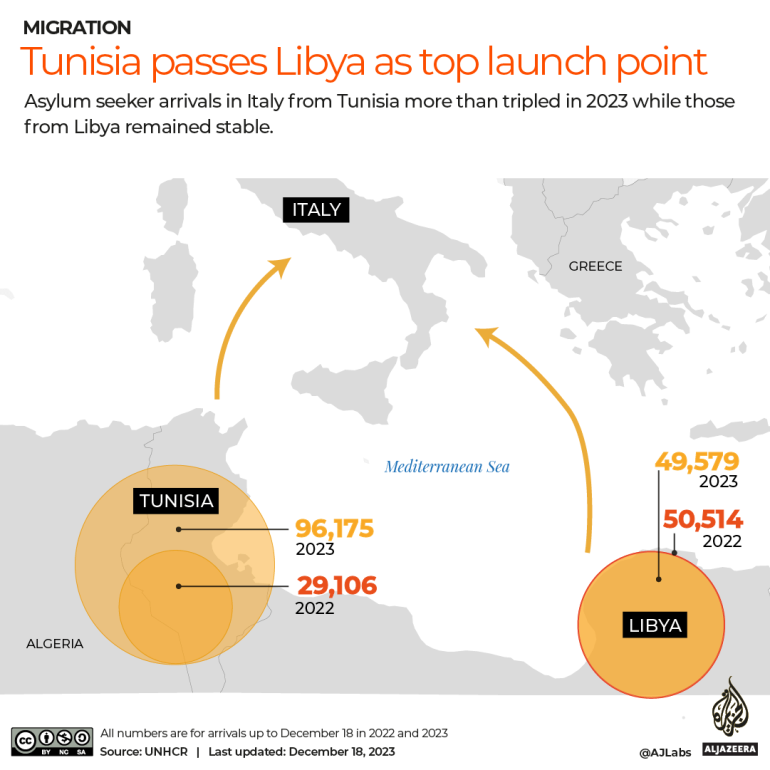

As Tunisia overtook Libya as the top embarkation point for people heading from Africa to Europe this year, EU officials struck a 1 billion euro ($1.1bn) deal to bolster the bloc’s capacity to prevent refugees from setting out to sea and stabilising Tunisia’s shaky economy.

Tunis was called to play a border patrol role similar to previous agreements struck with Tripoli and stop the inflow of refugees into European countries, months after President Kais Saied launched a crackdown against undocumented sub-Saharan nationals, whom he accused of crimes and plotting to change the country’s demographic makeup.

Tunisia’s poor economic situation and racial discrimination triggered an exodus towards European shores. “Tunisia used to be a country of arrival for sub-Saharan migrants, but racial discrimination has forced many to leave,” Di Giacomo said.

The UN estimated 96,175 people who reached Italy’s shores this year departed from Tunisia, compared with 29,106 last year.

Images of Italy’s southernmost island of Lampedusa receiving more than 6,000 people within 24 hours on September 12 prompted an visit by Meloni and von der Leyen, who pledged a crackdown on the “brutal business” of people smuggling and the swift repatriation of undocumented non-EU citizens.

About 70 percent of the people going by boat to Europe landed in Lampedusa, the IOM estimated. “The emergency this year has been only in Lampedusa, not in Italy. This is a logistical emergency, not a numerical one,” Di Giacomo said.

The deal struck with Tunisia falls squarely within the trends characterising EU cooperation on migration. Von der Leyen labelled the deal a “blueprint” for future arrangements, and the European Commission has anticipated that similar deals are in the pipeline with Morocco, Egypt and Sudan.

A call for a tender for search and rescue boats was completed in June for the delivery of three boats to Egypt, according to EU documents, and the second phase of a border management project worth 87 million euros ($95m) is expected to be contracted in the coming months.

Ibrahim Awad, director of the Center for Migration and Refugee Studies at the University of Cairo, told Al Jazeera that departures from the Egyptian coast are non-existent.

“What will the boats do? People do not migrate from the Egyptian coast but from Libya,” the professor said. “I don’t see the securitisation of migration to this extent to be effective in obtaining the objective of the European Union, which is to keep people from arriving.”

Meanwhile, NGOs operating in the Mediterranean said their search and rescue operations have been rendered more difficult by a series of laws passed by Meloni’s government that requires them to head to a port immediately after a rescue and disembark “without delay”. Yet the government typically grants access only to ports in central and northern Italy that are usually far away from the places of rescue and imposes administrative sanctions on those vessels that violate these norms.

“We continue to operate at sea, albeit in a very inefficient way, while the needs remain,” Giorgia Linardi, spokesperson for SeaWatch, told Al Jazeera. “Every government is devising its own strategies to curb our activities at sea while it’s the people in need of rescue who pay the price.”

An investigation conducted by a consortium of media organisations, including Al Jazeera, found that a vessel called the Tareq Bin Zeyad, linked to renegade Libyan General Kalifa Haftar, has been intercepting boats with asylum seekers at sea and taking them back to Libya. The eastern Mediterranean route saw a 50 percent increase in departures in 2023 compared with the previous year.

The investigation found that the European border agency, Frontex, was sharing coordinates with the vessel while internal documents revealed an attempt to brand the militia that runs the ship as a legitimate partner by formally labelling it part of the Libyan coastguard.

While the EU has argued that NGO rescues off Libya encourage traffickers, civil society organisations have long denounced the agreements signed with North African governments, which they said provide an incentive for human smugglers to arrange departures.

“The current policies do not curb human smuggling,” Linardi said. “They enrich smugglers who take migrants back to Libya and can profit from them another time round.”

Discussion about this post